|

On 25 March 2018, Uber Technologies Inc. was reported to have agreed to sell its Southeast Asian operations to Grab

I. Background E-hailing transportation services ventured into Malaysia in 2012 with two main competitors in the market: Uber and Grab.[1] These companies have made headlines multiple times over the last 6 years, especially for issues of the legitimacy of their operations and the insufficiency of regulations.[2] On 30 November 2017, the Land Public Transport (Amendment) Act 2017 and Commercial Vehicles Licensing Board (Amendment) Act 2017 came into force, which then legalised the operations of Uber and Grab as ‘intermediation businesses’.[3] Since then, both companies have been relatively uncontroversial until recently on 25 March 2018, when Uber Technologies Inc. was reported to have agreed to sell its Southeast Asian operations to Grab.[4] This was not the first ‘retreat’ by Uber in a regional market, having sold its business in Russia and China to Yandex NV and Didi Chuxing respectively.[5] The details of the agreement were undisclosed, however it was confirmed that Uber will take a 27.5% stake in Grab, and Grab will take over Uber's operations in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.[6] The agreement is also particularly beneficial for the biggest shareholder in both Uber and Grab – SoftBank Group Corp. – which avoids possible conflicts of interest since the competing rivals are now consolidated. The acquisition of Uber by Grab, or the ‘Uber-Grab merger’ raises several questions as to the nature of the agreement and whether it violates competition law. The after-effects of a merger which involves two major competing rivals in the same industry may lead to the monopoly of market and price fixing, which are issues of public interest. Assuming that the nature of the Uber-Grab deal is a merger, this article purports to discuss the jurisdiction of the Malaysia Competition Commission (MyCC) on mergers as well as possible issues of pricing and anti-competitive behaviour.

1 Comment

24/4/2018 6 Comments Lawyers and CommercialityI. Introduction

A long time ago, in the sanctuary of Delphi in ancient Greece, dignitaries, heads of states, military leaders and commoners alike would form snaking lines to seek advice from Pythia, the Oracle of Delphi. Access to the sanctuary was limited to only a few days over nine months in a year, and to overtake the long lines, great sums were paid by some for Pythia’s oracles. The advices, believed to be from the gods, were communicated in indirect and mysterious ways. This left many departing visitors to Delphi to try to decipher the meaning of the advices they had received. Now, as the threadbare paths and remains of Delphi are trampled upon by the hordes of modern tourists released by the busloads each day, some clients may be forgiven for thinking that they have chanced upon their own Pythia when they receive legal advice from their lawyers. In this article, I will discuss the importance of commerciality to contemporary commercial legal practice. Copyright refers to the right of the owner to control the doing of certain acts in relation to his or her created work Image credits: http://www.tannet.my/malaysia-copyright-protection/ I. Introduction

Copyright is a form of intellectual property. It is a legal term used to describe the rights that exist for the creators over their copyrighted work. An inference can be made that copyright was the first legal response to challenge new technology as it came into existence as early as the sixteenth and seventeenth century as a reaction to the rapid growth of moveable type printing presses which facilitated the production and distribution of printed materials. Prior to the rapid growth in the moveable type printing press in Johannes Gutenberg in what is now modern day Germany, rights involving creative works was never considered. Creative works were non-rivalrous despite existence and development of concepts relating to exclusiveness of property and goods. Throughout the glorious historic days of the Roman and Greek, written or spoken words were not covered by any sort of exclusivity. The notion of Green Sukuk owes itself to when socially responsible investments are made with regards to the environment.

Image credits: https://www.shine.cn/archive/business/UN-partners-with-Alibaba-for-green-finance/shdaily.shtml I. Introduction Before we indulge in the elucidation of Green Sukuk, the query that shall be first unfolded is the definition of Sukuk. Sukuk is an Islamic bond engineered to generate returns to investors without infringing the Islamic law prohibiting riba or interest.[1] It is an investment in the assets using Shariah principles and concepts endorsed by the Shariah Advisory Council. In the case of conventional bonds, the issuer has a contractual obligation to pay interest and principal to bondholders on certain specified dates. In contrast, when investors buy Sukuk, they become Sukuk holders and receive a certificate from the issuer to evidence ownership. Hence, they are entitled to receive periodic profit payments on the principal amount invested. Upon maturity, the Sukuk holder will be reimbursed the principal amount of investment.[2] This article aims to study the evolution and rise of Green Sukuk where the investment is specified to finance climate action projects. The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) was established in 2015 during the 27th ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

I. Introduction The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established primarily as a political bloc and security pact in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. ASEAN’s key objective was to promote intergovernmental cooperation and to facilitate economic integration among its member states, with the particular aim to enhance economic growth and trade respectively. At present, South East Asia is known to be one of the most open economic regions globally. This view is derived from the fact that ASEAN merchandise exports accounts for nearly fifty four per centum (54%) of the total ASEAN gross domestic product (GDP) which totals to approximately seven per centum (7%) of global exports.[1] To-date, ASEAN as an organisation has immensely helped its member states in achieving impressive economic growth as well as regional stability by working together harmoniously. Statistics show that between 2007 and 2015, the region has grown at an annual rate of 5.2 per centum and perhaps what is more astonishing is that the poverty rate in the region has declined for more than fifty per centum (50%), from thirty three per centum (33%) to fifteen per centum (15%) as early as 2000.[2] Due to these significant results, the member states of ASEAN realised that much more could be achieved if they operated as a single economic entity. Therefore, with the mutual aim to create a single free trade area for the region, the member states agreed to consolidate, integrate and transform ASEAN into a community called the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2007 – the mission was inspired by the regional integration established in Europe. AEC is directly expected to increase competitiveness, narrow development gaps and improve resilience against external shocks. In December 2015, the AEC was formally launched and established making the initiative the biggest single economic policy in Southeast Asia. Despite its establishment, there is a long journey ahead before the AEC can become fully functional. Acknowledging this, the ten member states have mutually agreed on a blueprint to complete the programme by 2025. The 2025 AEC blueprint consist of five pillars namely, single market and production base, competitive economic region, equitable economic region, integration into the global economy and enhanced connectivity and sectorial cooperation. It is to be noted that although the milestone achieved by ASEAN member states so far have been modest, the region faces immense obstacles concerning the process of economic integration. In this article, obstacles that ASEAN needs to overcome in order to achieve a fully functional economic community shall be discussed. 14/3/2018 1 Comment Mediation in the Syariah Courts:An Empowering Alternative for Amicable Resolution in Syariah DisputesMediation in Islam (Sulh) is an ancient idea but it is still relevant to our current needs. Image credits: https://farnfields.com/services-for-you/family-mediation/ I. INTRODUCTION

Mediation, also known as Sulh or Wasaatah in classical Islamic text, is not a foreign concept in the Islamic legal system as sources of Islamic law have consistently encouraged the endeavour for amicable settlement. In promoting peaceful conflict resolution, Muslim scholars have introduced approaches that are both systematic and fact sensitive. 10/3/2018 1 Comment The Spy Who Testifies - Quantum of Corroboration in Cases Involving Agent ProvocateursDoes an agent provocateur need to be corroborated under the law? I. Introduction

Does Malaysia have an intelligence agency like the CIA or MI6? States usually have their own method of operative centre for matters of intelligence and espionage. What if James Bond was an agent of our own intelligence agency? He would most certainly be an agent provocateur, or in other words, a spy, and not merely an informer. That being said, let there be a hypothetical situation in which Mr Bond and friends were to fumble and be called in the Malaysian courts – does Mr Bond then require corroboration for the evidence given during his testimony before the court? Surely this has never happened in the British film series – having the greatest spy of all times to testify in court as a botched operation always gets concealed in the end. However, in reality, case laws have established on whether it is necessary to corroborate an agent provocateur and an informer. This article provides a comparative analysis of the legal positions in the jurisdictions of Malaysia, United Kingdom and Singapore. 21/2/2018 1 Comment Freedom of Information in MalaysiaThe protection of freedom of information is still indeterminate in Malaysia

I. Introduction As the popular saying goes, “the control of information is the tool of the dictatorship.” Further reiterated by the European Court of Human Rights,[1] it is undisputable that access to information is crucial to the notion of transparency and good governance. The right to freedom of information is important for the access to government-held information, which concerns public interest. It is not only a right guaranteed under multiple international declarations and covenants,[2] but also a limb to the coveted right of freedom of expression.[3] Information relating to corruption of public officials, government development projects, embezzlement of public funds by officials, et cetera will not be available to the public without the right to freedom of information. This right is crucial for journalists worldwide as it champions press freedom and its power to report on any matter which the public has the right to know. With that, the public is empowered to monitor the integrity of the government and is assisted in making an informed choice in elections upon their scrutiny of government integrity. Despite international recognition, the protection of such a right in Malaysia is still indeterminate. A 1999 resolution endorsed by the Commonwealth Heads of Government, with Malaysia included, declared that the right to freedom of information should be guaranteed as a legal and enforceable right.[4] Malaysia is also a signatory to the ASEAN Declaration of Human Rights (ADHR) which endorses all rights stated under the UDHR, thus impliedly recognising the right to freedom of information.[5] However, the position taken by the legislative and the judiciary proves the contrary. E-commerce is a new form of business which heavily incorporates technology, and lawmakers need to keep up by enacting laws which are able to adapt in order to curb arising legal concerns. I. The Evolution of Electronic Commerce – A Brief Introduction We live in an era where almost everything is available in a digital form or at least undergoing a phase of digitalisation process. What digitalisation process simply means is that despite atoms can construct almost everything in the physical world, from a human kidney to a high speed train, bits, on the other hand, is the basic fundamental block of the digital world. The revolution of digitalisation started in the early 1980’s. The revolution was triggered as computers started moving into homes from workplaces and research laboratories. The first ever conventional media that embarked into, and adopted digitalisation, was the music industry on a business and logical sense that information converted from atoms to bits are generally cheaper to store and encode while significantly reducing the distribution cost. Technological advancement has grown and is continously growing on a rapid scale in recent years. This plays a direct link to the survival of most businesses. The most recent would be the fall of Nokia which has been successfully acquired by Microsoft. The direct and most apparent contributor to the acquisition was said to be the failure of Nokia to learn and keep abreast with technological changes that has led to their failure to survive. The Employment Insurance System Act 2017 (EIS) is an Act that aims to encourage the employees to seek re-employment apart from strengthening their employability in the labour market through placement programmes. I. Introduction

In 2015, more than 44,000 workers were retrenched due to various factors such as restructuring of the finance institutions, falling in the crude oil price and unstable ringgit currency.[1] In 2016, approximately 38,000 workers had lost their jobs with the majority of the lay-offs in manufacturing, trading, wholesale and retail, mining and finance sectors.[2] As a trading nation with an open market economy, Malaysia is no exception to the impact of shift in the economic structure from traditional economy to knowledge-based economy. Loss of employment, especially among low-skilled workers and labour-oriented industry is unavoidable. Among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), only Thailand, in 2004, and Vietnam, in 2009, had established an unemployment insurance scheme.[3] The existing Employment Act 1955 (“Act 265”)[4] only provides social security protection to the unemployed workers in private sector whose wages do not exceed RM2,000 or employees in West Malaysia with specific jobs as described in the First Schedule of the Act 265. Furthermore, the Minister of Human Resources (“Minister”) may provide termination benefits, lay-off benefits and retirement benefits to the employees by regulations made under the Act 265.[5] For instance, Employment (Termination and Lay-Off Benefits) Regulations 1980 (“Regulation 1980”) stipulates that an employer should pay termination or lay-off benefits to an employee who has been employed under a continuous contract of service for the past 12 months.[6] However, both the Act 265 and Regulation 1980 only provide a minimum amount of termination or lay-off benefits payment to the employees. The existing laws neither encourage the employees to actively seek re-employment nor strengthen their employability in the labour market. Hence, the Employment Insurance System Act 2017 (“Act”), passed by the Dewan Rakyat on 25 October 2017, the Dewan Negara on 18 December 2017,[7] and came into force on 1 January 2018,[8] is a timely yet comprehensive law to protect the workers in Malaysia. The Act sets out provisions to provide certain benefits and a re-employment placement programme for insured persons in the event of loss of employment which will promote active labour market policies. This article provides an overview of the Act. 20/1/2018 1 Comment Can a Mere Exclusion Clause be Considered an Ouster of the Court's Jurisdiction?There are situations where one party would unfairly impose an exclusion clause that protects them from any liability whatsoever in the event of a breach of contract

I. Introduction A recent Federal Court Appeal[1] of a suit between an established local bank and two of its customers is generating slightly more than the usual interest in the normally staid realm of Contract Law. That the case should involve an exclusion clause is hardly surprising given the backdrop of judges’ often unfavourable views of the role of such clauses in a contract. Legal arguments involving the principles of fundamental breach and the contra proferentum rule have been accepted by judges to restrict the one-sided and arguably, often unfair application, of widely drafted exclusion clauses. Lord Diplock in his judgement in the case of Photo Production Ltd v Securicor Transport Ltd said “…the reports are full of cases in which what would appear to be very strained constructions have been placed upon exclusion clauses,…”[2] Notwithstanding such adverse perception, exclusion or limitation clauses can be regarded in one of two ways. On one hand, such a clause is often considered to be a means for the parties to apportion liability under the contract, and is said to reflect the intention of the parties in doing so. On the other hand, such clauses are often inserted into a contract by the stronger party to exclude all possible liabilities under the contract on the part of that party. In many of the latter cases, it would appear that the innocent party would have no recourse for the losses suffered caused by the breach or other wrongful conduct of the other party by virtue of the wide exclusion clause in the respective contract. In cases involving many consumer contracts, the Parliaments in Malaysia and the UK have legislated to provide a measure of protection to consumers. In Malaysia, Section 24 of the Consumer Protection Act 1999 gives protection to consumers who “acquire[s] goods or services of a kind ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household purpose, use or consumption…”[3] However, it is often in those cases involving contracts not governed by such legislations, and where it appears that one party had unfairly imposed an exclusion clause that basically protects them from any liability whatsoever in the event of a breach of contract, that invites strict scrutiny from the courts. The recent Court of Appeal decision in Anthony Lawrence Bourke And Another v CIMB Bank Berhad (“Bourkes v CIMB”)[4] would appear to be such a case, whereby the court may have felt compelled to intervene judiciously in the application of such an exclusion clause. ADR is popular in many jurisdictions no longer as an alternative form of dispute resolution, but rather as a primary mechanism.

I. The Development of ADR – A Brief Overview Alternative Dispute Resolution (‘ADR’) is evidently not a new phenomenon. Societies have been developing informal and non-adversarial processes for centuries to resolve disputes. As a matter of fact, archaeologists have discovered evidence that ADR processes were used in ancient civilisations particularly in Egypt, Mesopotamia and Assyria.[1] To-date, one of the earliest recorded mediations occurred over four thousand years ago in the ancient society of Mesopotamia. It was discovered that the then Sumerian ruler used a mediation process to help avert war and subsequently developed an agreement in a dispute over land.[2] There are many examples where ADR processes were developed in traditional societies as a mechanism to resolve disputes. The Bushmen of Kalahari, native people of Namibia and Botswana, developed sophisticated systems in order to resolve disputes’ arising that avoids physical harm and the courts. William Ury held that “when a serious problem comes up everyone sits down – all the men, all the women – and they talk, and they talk and they talk. Each person has a chance to have his or her say. It may take two or three days. This open and inclusive process continues until the dispute is literally talked out.”[3] In China, since the Western Zhou Dynasty approximately two thousand years ago, the post of a mediator has been included in all governmental administration. Today, it is estimated that there are 950,000 mediation committees in China, with at least six million mediators. The said committees handle between ten to twenty million cases annually, ranging from family disputes to minor property disputes. Similarly, in India there has also been a long tradition of using ADR as a tool to resolve disputes. The most adopted and used method of dispute resolution, ‘panchayat’, came into existence somewhat 2500 years ago and was widely used to resolve both commercial and non-commercial disputes. In the western world, the development of ADR can be traced to the ancient Greeks. A public arbitrator position was introduced by the city-state around 400 B.C as the Athenian courts became overcrowded. Today, ADR is popular in many jurisdictions no longer as an alternative form of dispute resolution, but rather as a primary mechanism. ADR has flourished to the point where it has been suggested that the adjective should be dropped altogether and that ‘dispute resolution’ should be used to describe the modern range of dispute resolution methods and choices.[4] The two most common forms of ADR in this era consist of mediation and arbitration. 24/12/2017 81 Comments RegTech World Tour: Asian ChapterOn 23rd November 2017, Quanta RegTech Capital (QRC) in collaboration with Infinity Blockchain Labs (IBL) embarked on the Asian leg of its RegTech World Tour in Ho Chin Minh City to acquaint the global community with RegTech. The kick-off event was attended by representatives from varying sectors but principally consisted of those from the corporate and legal sector. The session was allocated to four speakers who spoke about RegTech from different perspectives, all of which are highlighted in this report.

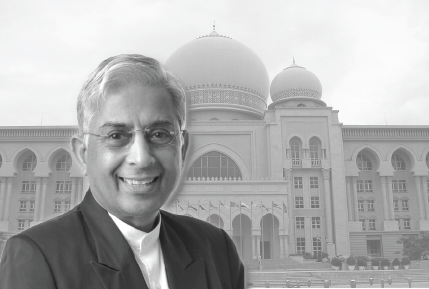

I. WHAT IS REGTECH? Adam Vaziri, co-founder of Diacle aptly began with a short introduction to RegTech. ‘RegTech’ or regulatory technology, was described as being the use of technology to facilitate compliance in regulated industries. RegTech not only addresses the needs of regulated businesses, but also the needs of regulators or governmental agencies as well. The advent of FinTech resulted from the acknowledgement of the shortfalls in the traditional risk assessment regime in the financial industry, which was particularly palpable after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Unlike in Fintech, there is no pivotal event where the introduction of RegTech is concerned. However, its introduction is also the consequence of a realisation that the existing systems in regulatory compliance are inadequate and can be much improved. After receiving Royal Assent on 9 October 2017, the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) (Amendment) Act 2017 still awaits its date of commencement in the Federal Gazette. I. Introduction Unilateral conversion of minors is not a rare phenomenon in a multi-religious nation like Malaysia. Over the recent years, news regarding the conversion of children to Islam by their converted parent without the consent of the other parent has caught the attention of the public. Although a few high-profile cases were brought before the courts in the past, there is yet a solid solution to this increasingly frequent controversy as of now. In 2007, Subashini lost the custody of her elder son to her Muslim-convert husband, who converted the child without her knowledge, when the apex court ruled that either party to a marriage has the right to convert a child to Islam.[1] Almost a decade later, S Deepa found herself in a similar predicament, when the Federal Court followed the 2007 landmark decision.[2] The series of unilateral conversion cases, however, did not stop there. Following the more recent case of Indira Gandhi,[3] the longstanding controversy over the unilateral conversion of minors to Islam finally prompted the government to amend the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976.[4] Aiming to also settle disputes regarding the legal rights of the both converting and non-converting spouses and the custody of children, Datuk Seri Azalina Othman Said, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department, tabled the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) (Amendment) Bill 2016 in November 2016.[5] With five amendments and two new provisions, the long-anticipated bill is undoubtedly a breakthrough in the Malaysian family law. Professor Emeritus Datuk Dr Shad Saleem Faruqi is the holder of the Tunku Abdul Rahman Foundation Chair

I. CONCEPT OF A LEGAL SYSTEM A legal system refers to the overall legal regime of a country. It provides institutions, principles, rules and methods for regulating the relationship between law and society. It describes law’s connection with authority and with morality. It describes the sources from which the law springs. It provides the procedures and methods for making law and resolving disputes. It encompasses the institutions, principles and procedures for the exercise of power and the limits thereon. It includes a set of laws and the manner in which the laws are interpreted and enforced. It outlines the rights, responsibilities, and duties of citizens towards each other and towards the state. It provides for the imposition of punishments. It provides for the classification of laws into various categories (civil law and criminal law, public law and private law, procedural law and substantive law, the law of tort and law of contract) and the differences and similarities between these categories. Over the millennium, the world has known many types of legal systems. The oldest were built on custom and religion. In modern times, it is believed that there are six primary categories of legal systems; civil law systems, common law systems, religious systems, customary systems and supranational systems, and mixtures of the five. The choice of one or the other is affected by history, politics, and social traditions. 25/11/2017 8 Comments Legal Profession in the Age of Disruption: 5 Key Discussions in 'LexTech Conference 2017'LexTech Conference 2017 is a regional legal conference gathering Southeast Asia's leading legal technology futurists.

News about the rise of revolutionary and industry-changing legal technologies (“Lextech”) have swept the globe and rightfully caused a great deal of unease among members of the legal profession in Malaysia. On the 4th and 5th of November, current and future members of the legal profession and regional leaders in the Lextech industry converged in Cyberjaya for the Lextech Conference 2017, titled ‘The Future of Law’, co-organised by CanLaw and Brickfield Asia College. Many came to the conference looking for answers, which the panel of esteemed, experienced, and accomplished speakers tried their best to provide. A broad array of topics, ranging from Lextech, Blockchain, Smart Contracts, Artificial Intelligence, and the future of the legal industry were discussed in depth. This article aims to give a detailed overview of the 5 key areas of discussion during the event. I. Introduction

On the 20th of December 2016, the Federal Court in Putrajaya reversed the decisions of both the Court of Appeal and High Court of Sibu in the case of Director of Forest, Sarawak & Anor v TR Sandah & Ors[1]. The appellant in the case was the State Government while the Respondents were the Ibans and natives of Sarawak. The respondents claimed Native Customary Rights (NCR) over 5,639 hectares of land which the Respondents and their ancestors inherited by virtue of the Iban custom of pemakai menoa and pulau galau. The subordinate courts initially granted the Respondents NCR over the claimed area of land in Kanowit-Ngemah, Sarawak before the Federal Court reversed the decision and deprived the natives of their NCR. This commentary aims to simplify and analyse the judgment made in the Federal Court regarding the TR Sandah case and its impact onto the natives of Sarawak’s rights to land. After receiving Royal Assent on 10 May 2017, the Bankruptcy (Amendment) Act 2017 came into force in Malaysia on 6 October 2017

I. Introduction The new Bankruptcy (Amendment) Act 2017,[1] which came into force on 6th October 2017, has renamed the existing Bankruptcy Act 1967 [2] as the ‘Insolvency Act 1967’.[3] The new Act will bring about significant changes to the law and, along with these, possible uncertain ramifications. In general, the changes provide increased protection for individual debtors, by allowing them more opportunities to restructure repayment of their debts. The increased protections are a response to the worrying trend of significant increases in the number of reported bankruptcy cases. One of the underlying objectives sought to be achieved is to create a society (comprised as it is of debtors and creditors) which is more financially literate on the issue of debt repayment. The Panel of Judges was headed by Danial Feierstein (left) in deliberating the trial. (Source: Bernama)

Religious superiority has long been one of the bases for the marginalisation and persecution of ethnic minorities. For the very same reason, the sufferings of the Muslim community in Myanmar continue to be a long, dark abyss towards annihilation. Their cries, although widely heard and reported by international media and agencies, do not change the fact that they remained oppressed by the Myanmar extremist Buddhist government. It does not help that the supposed beacon of hope, hiding behind her Nobel Peace Prize, is now the icon of hypocrisy and irony. As the Muslim minorities’ identities are being diluted in the country’s diverse social fabric, efforts to obliterate their physical presence have manifested in nefarious acts of abuse and violence against men, women and children alike. Among the execution strategies adopted by the state of Myanmar towards its marginalised include; mass razing of homes and villages, forced evacuation, murder and rape, all of which have been commented upon by the United Nations as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.[1] Despite facing years of condemnation and massive criticisms by the international community, the Myanmar government is resolute in its standing of innocence; an outright lie to the face of justice. Even so, the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal attempted to shine some light at the end of the tunnel for the Muslim minority community in a trial held at the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya. The trial lasted from 18th to 22nd September 2017. I. Introduction

Based on currently available information, Malaysia and North Korea’s diplomatic ties spanning four decades was gravely damaged when Kim Jong Nam, the estranged brother of Kim Jong-un was assassinated at KLIA on 13th February 2017. Tensions between the two countries escalated when the North Korea ambassador, Kang Chol, criticized the handling of the case by Malaysian authorities, even going as far as to accuse Malaysia of being untrustworthy and colluding with other nations to defame North Korea. [1] As a result, he was declared a persona non grata[2]—likely the first of which has ever happened to a diplomat stationed in Malaysia—and therefore, expelled from the country. Persona non grata, which is provided for in Article 9 of the Vienna Convention of Diplomatic Relations 1961, an international convention to which both Malaysia and North Korea are parties to, allows a receiving state to “notify the sending State that the head of the mission or any member of the diplomatic staff of the mission ... is not acceptable.” At which point, “the sending State shall, as appropriate, either recall the person concerned or terminate his functions with the mission.”[3] If the sending State refuses or fails within a reasonable period to carry out its obligations to recall the person, the receiving State may “refuse to recognize the person concerned as a member of the mission.” [4] In other words, the foreign diplomat would no longer be welcomed in the receiving state, nor would they continue to enjoy diplomatic immunity under the Vienna Convention. Declaring a diplomatic staff as persona non grata could be considered to be one of the harshest diplomatic measures[5] a state can take against another state. Not surprisingly, North Korea retaliated by similarly declaring Malaysia’s ambassador, Mohamad Nizan Mohammad, a persona non grata[6]. Soon after, North Korea decided to impose a travel restriction on Malaysians who are in their country[7], from leaving North Korea. In retaliation, Malaysia has decided to do the same shortly after the decision was made to North Koreans who are currently in this country[8]. The Malaysian Prime Minister, Najib Razak, in announcing the retaliatory travel ban, released a statement stating that North Korea’s act of holding Malaysian citizens as “hostages” [9] is in “total disregard of all international law and diplomatic norms.” [10] However, this begs the question, is the decision to ban foreign citizens from leaving one's country (be it North Korea or Malaysia) a breach of human rights and/or in compliance with international law? This article aims to study the relevant treaties under international law with regards to the travel ban and to determine if any breach of international law was committed by both Malaysia and North Korea. 21/2/2017 4 Comments Company Law Reform - A Guide to the Changes in the Malaysian Companies Act 2016 I. Introduction

After a long wait, the much-anticipated Companies Act 2016 has finally come into force on 31st January 2017 replacing the 1965 Act, which has been around for more than half a century. Incorporating new provisions and amendments, the whole Act has overhauled its content from a 374 sections’ Act to a 620 one. This article aims to give a broad overview of the differences between the old act and the new act and its implications. I. Introduction In the critically acclaimed book ‘The World Without Us’[1], readers were asked to envision our Earth, if all humans were to disappear tomorrow. In breathtakingly detailed paragraphs, the author explained how our massive infrastructures would collapse, the ozone layer would replenish, ultraviolet levels subside and flora and fauna would reclaim the earth– a “paradise”. In his closing, author Alan Weisman writes; “Without us, Earth will abide and endure; without her, however, we could not even be.” To Malaysia’s credit, issues regarding the environment have, in the past years, been an agenda close to the heart of our judiciary, especially of our Chief Justice, Tun Arifin Zakaria. Since his appointment as Chief Justice of Malaysia in 2011, he has been active in furthering the environmental cause both nationally and regionally. Under his leadership, Malaysia’s judiciary has seen heartening initiatives[2] such as the establishment of two environmental courts, active participation in regional judicial commitments such as the ‘Jakarta Common Vision’ and increased training and education for the members of our Judiciary to implement such commitments. In his speech at the Opening of the Legal Year 2017[3], he brought his activism one step further when he recommended that the Federal Constitution be amended to include a right to a clean and healthy environment. The Chief Justice praised as ‘generous and accurate’ the landmark Court of Appeal judgment of Datuk Seri Gopal Sri Ram in the 1996 case of Tan Tek Seng v Suruhanjaya Perkhidmatan Pendidikan[4] which stated that the right to live in a reasonably healthy and pollution free environment is implicit in Article 5 of the Federal Constitution[5], which guarantees the right to life. This article aims to look at the status quo of Environmental Law in Malaysia, access our progress in the area according to established yardsticks such as the Environmental Democracy Index[6] and identify areas for improvement with suitable recommendations. 25/11/2016 1 Comment Law & Society - An Analysis on the Influx of Foreign Workers and Human Trafficking in MalaysiaI. Introduction

Statistic shows that the number of legal foreign workers in Malaysia amounted to 6.9% of Malaysia’s population of 30 million.[1] The number of foreign workers in Malaysia is so vast that it is equivalent to one-third of the population of Singapore (5.5 million). However, alarmingly, the actual number of foreign workers could be much higher, in 2014, the United States of America had downgraded Malaysia to tier 3 in its annual Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP)[2]. Malaysia's relegation to Tier 3 in the TIP indicates that the country has categorically failed to comply with the most basic international requirements to prevent trafficking and protect victims within its borders.[3] Malaysian ranking in the international platform is justified by various evidences of forced labour, and prostitution occurring throughout the country. 1/11/2016 0 Comments Criminal Law - The Case for Introducing Restorative Justice into the Malaysian Criminal Justice SystemI. Introduction of Restorative Justice Practice

The traditional criminal justice system focuses solely on the offender, and how to punish him or her to create a deterrence effect both for that particular offender and for potential offenders within society. At the same time, the system excludes the victims of the crime who are only regarded as witnesses to help the prosecutor prove that the offender is guilty of an offense. This practice has resulted in a disheartening weakness in the current criminal justice system. Subsequently, after much soul searching and research, a new paradigm of justice known as restorative justice emerged. Restorative justice has been widely developed and applied in many countries to handle crime. Recently, it has developed sporadically in various ways, following from its first experimental inception in North America and subsequently spreading to European and Asian countries. 21/10/2016 4 Comments Law and Society - An Analysis on the Implementation of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in the Process of Obtaining Approval for Logging Permits on Orang Asli Land in MalaysiaI. Introduction

On the 26th of November 2015, an application for logging permits on gazetted land allocated to Orang Asli was filed and granted by the State Executive Council in Jerantut, Pahang. However, there were allegations that the granting procedure did not incorporate the consent needed from the local Orang Asli community. Instead, pecuniary ‘gifts’ were given to each household as well as a certain sum of ‘donation’ to the local community funds. Albeit such ‘gifts,' a few joint rallies have been organized by the affected parties such as the Malays as well as the Orang Asli communities residing around the compartment areas against the land development. This conflict between the developers and the local community is especially prominent in Kg. Sg. Kiol as due to the ongoing activities of logging, the Orang Asli living in Kg. Sg Kiol has suffered from contaminated water sources, trespass of land, loss of forest resources and threats from wild animals whose habitat had been destroyed by logging. This case study aims to analyze the implementation of free, prior, and informed consent in regards to the land rights of Orang Asli residents in general. |

CategoriesAll Comments Criminal Law Environmental Law Law And Society UMLR |

Search by typing & pressing enter