|

16/9/2019 2 Comments Dilution of Banker's Duty of Secrecy in Malaysia under the Financial Services Act 2013: An Adventure Too Far?A banker’s duty of secrecy has been statutorily codified even in predecessing statutes prior to the coming into force of the Financial Services Act 2013 ('FSA'). The FSA has allowed for a wide scope of permitted disclosures of customer information, and this superficially constitutes a major inroad into the duty of secrecy owed by bankers to their customers. I. INTRODUCTION Swift fly the years, it is 2019 and the Financial Services Act 2013 (‘FSA’)[1] has just celebrated its sixth birthday. This piece of legislation was intended to boost Malaysia’s financial sector, which encompasses the banking system, the financial markets and other financial intermediaries.[2] Over the past six years, we have seen the gradually robust implementation of the FSA. However, lurking in the shadow is the issue of a banker’s duty of secrecy towards customers, which received statutory codification way back in the FSA’s predecessor statutes. The coming into force of the FSA allowed for a wide scope of permitted disclosures of customer information, and this superficially constitutes a major inroad into the duty of secrecy owed by bankers to their customers. Yet, the government and other stakeholders of the financial sector are always quick to assure the masses that such dilution is justified and necessary. Therefore, this article seeks to examine the current legal position on the banker’s duty of secrecy under the FSA and scrutinise the prescribed permitted disclosures. The author will then analyse whether the considerable amount of statutory exceptions dilute the duty of secrecy and whether there are justifiable grounds for such dilution. Before concluding the article, the author will also briefly look into the Personal Data Protection Act 2010 to see whether it addresses or exacerbates the dilution. It must be noted that the focus of this article is only on the FSA and does not include the relevant provisions in the Islamic Financial Services Act 2013.[3] II. THE TRADITIONAL DUTY OF SECRECY AT COMMON LAW Secrecy is the cornerstone of confidence in the banking system. Members of the public must have confidence in the safety and secrecy of their accounts as well as their bankers’ integrity and professional conduct. Historically, it was not until the cardinal common law case of Tournier v National Provincial and Union Bank of England (‘Tournier’)[4] that English law firmly placed an implied duty of secrecy of customer information onto bankers. In Tournier, the claimant, whose account with the defendant bank was heavily overdrawn, failed to meet the repayment demands made by the bank manager. On one occasion, the manager noticed that a cheque, drawn to the claimant’s order by another customer, was collected for a bookmaker’s account. The manager then disclosed to the employers that the claimant was not paying off his overdraft but had instead endorsed a cheque in favour of a bookmaker. In consequence, his employers refused to renew his employment contract. The English Court of Appeal delivered a landmark decision by holding that every banker has an implied duty to keep its customer’s information confidential. However, this duty is not absolute; it is subject to four circumstances wherein disclosure of information by banks is:

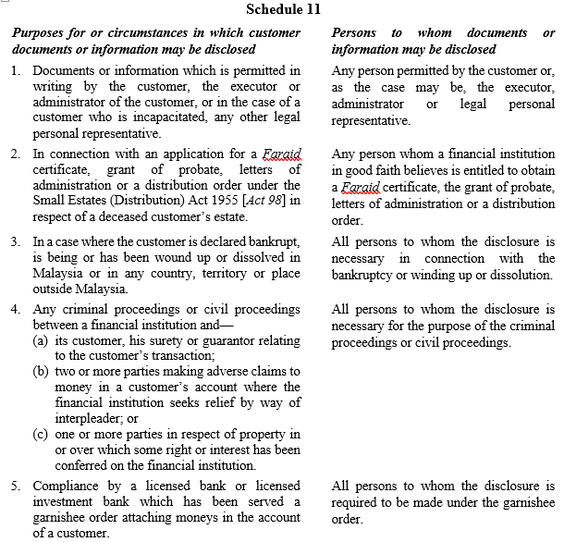

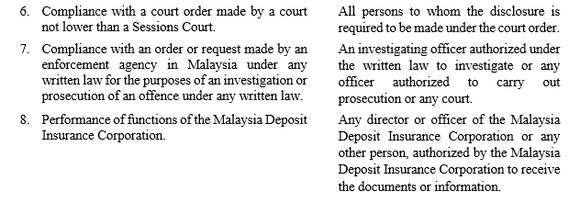

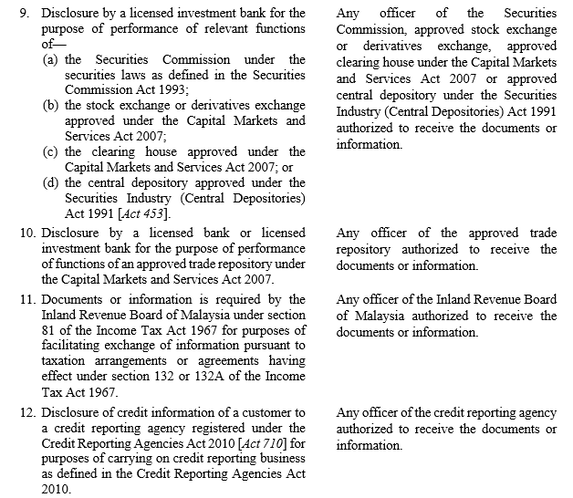

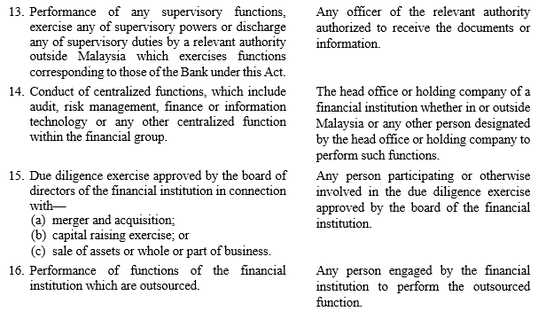

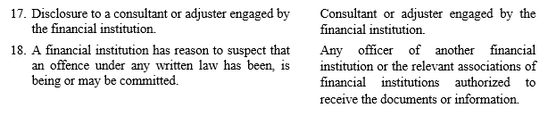

III. DUTY OF SECRECY UNDER FINANCIAL SERVICES ACT 2013—A FALTERING DUTY In Malaysia, this implied duty was codified in the Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989[5] (‘BAFIA’) where the general rule of secrecy was laid down in S.97. The law has since been repealed and replaced by the FSA and its S.133 provides for the general rule of secrecy. S.133(1) of the FSA stipulates that no person who has access to any document or information relating to the affairs or account of any customer of a financial institution, including the financial institution or any person who is or has been a director, officer or agent of the financial institution, shall disclose to another person such document or information. With that, the duty of secrecy requiring a banker to keep information relating to a customer’s account confidential is statutorily codified in our latest statute governing bankers. Similar to its predecessor the BAFIA, S.134(1) of the FSA prescribes permitted disclosures for circumstances embodied in Schedule 11, or if approved in writing by BNM. Many of the exceptions in S.98 to 102 of the BAFIA have found their way into Schedule 11 of the FSA. In addition, a wider set of circumstances where disclosure is permitted is stipulated. For the ease of discussion, the author herewith reproduces Schedule 11 of the FSA: A brief perusal of Tournier and S.133 superficially reveals a close parallel between the statutory duty imposed by the FSA and the common law duty of secrecy as established in Tournier. There are, however, significant differences if we turn the limelight from the general prohibition against disclosure to the exceptions to the general prohibition. The author will compare the statutory exceptions in Schedule 11 with the four exceptions set forth in Tournier:

IV. JUSTIFIABILITY OF THE PERMITTED DISCLOSURES—LOOKING FOR THE SILVER LINING The comparison between Schedule 11 and Tournier’s exceptions seems to reveal that the statutory exceptions provided under Schedule 11 are narrower than those available at common law, with duty to public to disclose and implied consent finding no parallel. However, Schedule 11 allows for disclosure for purposes that are not ordinarily authorised under common law exceptions. For instance, customers’ credit information to credit reporting agencies [Para 12], centralised function within financial group [Para 14], merger, acquisition and capital raising [Para 15], outsourcing [Para 16], consultant or adjuster engaged [Para 17], and suspicion that an offence may be committed [Para 18]. One may argue that these categories fall under the exception of disclosure made in the bank’s interest. However, Professor Ellinger argued that the scope of this exception should be kept within a fairly narrow confined, not extended to include the bank’s commercial convenience and advantage.[10] The author hence wishes to evaluate whether the large number of exceptions in Schedule 11 dilute a banker’s duty of secrecy, and if it does, whether such dilution is justifiable. The author also may add that he is happily spared the task to deal with the grounds listed in Schedule 11 that are parallel to the Tournier’s four exceptions (and the fifth ground by Professor Ellinger). The cynosure of the discussion will be on selected permitted disclosures that are freshly introduced in the FSA but not explicitly addressed by Tournier. A. Enforcement agencies for criminal investigation—Para 7 The scope of this exception is relatively much more extensive than that laid down in Tournier.[11] Over recent years, the amount of legislations permitting enforcement agencies to order the inspection or disclosure of bank documents has burgeoned, making major inroads into the banker’s duty of secrecy. For example, Malaysia has penalised tax evasion under the Income Tax Act 1967,[12] stock-market manipulation and insider trading under the Capital Markets and Services Act 2007,[13] and domestic bribery and corruption of foreign public officials under the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2009.[14] Thus, eligible law enforcement agencies snowball to include the Royal Malaysian Customs Department, the Inland Revenue Board of Malaysia, the Securities Commission, the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission and more. When Parliament enacted new legislations to combat fiscal offences, it is indeed true that there was no creation of new head of exceptions as Tournier itself already allowed such disclosure required by law. However, in reality, those new crimes dilute bank secrecy in respect of conducts which were not previously criminalised in Malaysia and approve new enforcement agencies to acquire and cumulate customer information, hence giving greater content to the horizon of this exception. The rationale behind the constant opening of a new avenue to access customer information is that financial crimes are frequently cloaked in secrecy. Hence, the banking system may inadvertently conceal or facilitate criminal purposes. Various forms of financial system abuse may have multi-faceted negative consequences, such as the compromising of financial institutions’ reputation, the undermining of investors’ trust in them and the impairing of the financial system. Clearly, the expansion of the ambit of this exception is necessary; in future, its range is likely to increase to further protect the integrity of the national financial system. As a side note, Para 18, supplementary to Para 7, prescribes that disclosure is permitted if “a financial institution has reason to suspect that an offence under any written law has been, is being or may be committed”. It can disclose to officers of another financial institution or relevant associations authorised to receive the information. This is, again, not overreaching as financial institutions should be imposed obligations to monitor their clients’ activities and report suspicious transactions, provided that they must have good grounds for such suspicion. 1. Anti-Money Laundering, Anti-Terrorism Financing and Proceeds of Unlawful Activities Act 2001 The author wishes to highlight the Anti-Money Laundering, Anti-Terrorism Financing and Proceeds of Unlawful Activities Act 2001[15] (‘AMLA’) where the overriding of banking secrecy can be most clearly witnessed. The present ambit of AMLA encompassing various financial crimes is extremely wide, with 356 offences under 42 pieces of legislations listed under the Second Schedule.[16] Passed in 2001, AMLA was meant to combat money laundering. Later, there were amendments in 2007 and 2013 to confer wider powers on enforcement agencies to combat terrorism financing and to deal with proceeds of unlawful activity respectively. Serious offences envisaged under AMLA consist of those criminalised under different areas of law. Selected offences under Dangerous Drugs Act 1952,[17] Customs Act 1967,[18] Copyright Act 1987,[19] Child Act 2001,[20] Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007,[21] International Trade in Endangered Species Act 2008,[22] and Wildlife Conservation Act 2010[23] prescribed in the Second Schedule of AMLA are amongst those considered as unlawful activities. If a person engages in a transaction that involves proceeds from an unlawful activity, he will be deemed as engaging in money laundering, thus committing an offence under S.4 of AMLA. S.5(1)(b) of AMLA then provides that where a person discloses to an enforcement agency his knowledge of or belief in a money laundering offence, his disclosure shall not be treated as a breach of any legal restriction on the disclosure of information. Besides, S.20 of AMLA stipulates that the disclosure shall have effect “notwithstanding any obligation as to secrecy or other restriction on the disclosure of information imposed by any written law or otherwise”. AMLA best reflects the effect of Para 7 on banking secrecy. While Para 7 is regarded to be within the exception of disclosure required by law, its horizon has been expanding significantly to the extent that bank secrecy is considerably diluted. Nonetheless, the author proposes that this dilution is unassailable to protect the reputation of the Malaysian financial system by prohibiting bankers from, either actively or passively, assisting in flight capital, tax evasion and serious crimes including terror attacks, money laundering, child kidnapping, drug trafficking as well as wildlife smuggling. These financial crimes are multi-faceted, thus the increase in legislations that intrude upon the duty of secrecy is necessary for the detection and prosecution of criminals, and to ensure that the banking system is not manipulated by criminals in any way. The integrity of the banking systems must be well protected, lest public confidence in the systems diminishes.[24] B. Credit Reporting Agencies—Para 12 Another new area of intrusion into the traditional banker’s duty of secrecy has been opened by Para 12, where a banker is permitted to provide credit information of a customer to a credit reporting agency registered under the Credit Reporting Agencies Act 2010 (CRAA 2010).[25] The CRAA 2010 facilitates to reduce the asymmetric information between the credit providers and potential borrowers, though the decision to grant the credit lies solely with the respective credit provider. Prima facie, Para 12 camouflages as another dilution of banker’s duty of secrecy where a credit reporting agency may collect and use customers’ information from banks to prepare a credit report to assess their credit worthiness, including credit card accounts, mortgages and car loans, history of bankruptcy and history of failure or diligence regarding repayments.[26] As was held in the English case of Turner v Royal Bank of Scotland,[27] such disclosure of information constitutes a breach of the banker’s duty of secrecy. However, the author proposes that the CRAA 2010 is, in effect, safeguarding customers’ interest and information. Prior to the enforcement of the CRAA 2010, there was no specific control over the practices of credit reporting agencies in collecting and processing credit information.[28] These behind-the-scenes and unsupervised activities caused individuals inconvenience and hardship, especially when inaccurate details regarding their creditworthiness were provided to banks approached by these individuals for loans.[29] With the celebrated gazetting of the CRAA 2010, credit reporting agencies are now under the regulatory oversight of the Ministry of Finance. Statutory measures taken to preserve customer’s interest under the CRAA 2010 include:

Even if one argues that dilution does exist, Professor Ellinger proposes that such disclosure by banks, without customer’s consent, to credit reporting agencies can be justified by the banker’s own interests, that is, to maintain the integrity of the credit reference system so that the bank can rely upon it with confidence when seeking information of a potential customer or borrower in future.[30] However, his concern towards this approach is that such interpretation will be too liberal to include commercial convenience and advantage as banker’s interest. Thus, Professor Ellinger prefers the approach taken by Judge Rudd—which the author agrees—by justifying such disclosure due to the existence of a public duty on the banker. He reasoned that due to the current global credit crisis, modern consumer society is very dependent upon the availability of credit and hence, it is in the general public interest that such credit should be provided responsibly.[31] C. Centralised function within the financial group—Para 14 The cardinal principle of separate legal personality has been firmly established in the common law since the decision in Salomon v Salomon.[32] This bedrock feature of company law propounds that each company within a corporate group must be regarded as a separate and independent entity. Thus, disclosure of confidential customer information by a bank to a parent or subsidiary company in the financial group will, at common law, breach the bank’s duty of secrecy. The author is of the view that the law should allow the disclosure of customer information between banking companies in the same group so long as it is reasonably necessary to enable banks to meet their statutory obligations within the banking group. However, sharing information for marketing purposes is not justifiable even if the banking group would run in a more efficient and cost-effective manner as a result. Justifying disclosure of customer information through the bank’s commercial convenience and advantage is flawed and unwarranted. In Malaysia, Para 14 allows the disclosure of customer information for the conduct of centralised functions, which include internal audit, risk management, finance or information technology within the different entities of the same financial group. BNM has prescribed specific requirements on this permitted disclosure. For the avoidance of doubt, BNM plainly defines ‘centralised functions’ as functions established at a regional office or the head office for the purposes of group oversight and compliance with regulatory requirements, excluding any ad hoc assignments or one-off activity.[33] In the Malaysian context, disclosure of information for the purpose of centralised function within the financial group is not for commercial benefit or convenience but specified only for the compliance with regulatory requirements. Hence, it is justifiable and falls under the Tournier’s exception of disclosure for the bank’s interest. D. Outsourcing—Para 16 BNM has issued a policy document on governance and risk management standards of outsourcing, effective since 1 January 2019.[34] The policy document defines ‘outsourcing arrangement’ as an arrangement in which an outsourced service provider performs an activity on behalf of a banker on a continuing basis.[35] Examples of such arrangement include system or application leveraging, data center hosting, data center operations, data storage, cloud computing services and back-up location. Recently, outsourcing has become a critical component of financial institutions’ management of their business operations and control of their costs. Owing to the significant transformation of the Malaysian financial landscape, outsourcing arrangements is increasingly used as a means to improve business agility. However, permitted disclosure under Para 16 to a person engaged by the financial institution to perform outsourced functions, again, raises concerns on the compromising of data integrity and secrecy of customer information, where adverse effects may follow on the standing of bankers as custodians of public funds. Nevertheless, the author avers that the increase in complex and sensitive banking operations render outsourcing necessary to help financial institutions supplement internal resources, address skill gaps and strengthen core business processes.[36] Outsourcing can exploit new financial technology while mitigating technological risk[37] to improve overall business performance. Eventually, customer service will be enhanced when customers reap the benefits generated from outsourcing. Besides, the policy document issued by BNM mandates bankers to ensure that appropriate levels of controls, governance, policies and procedures are in place and are effective in safeguarding the security, confidentiality and integrity of information shared under the outsourcing arrangement. Security controls include:[38]

E. Engagement of consultant or adjuster—Para 17 Being an exception freshly introduced in the FSA, Para 17 allows for disclosure of customer information to a consultant or an adjuster engaged by the financial institution. A consultant refers to any person who provides professional advice and independent assessment or services on a particular field of expertise to financial institutions on a temporary basis for a fee,[39] for instance, in the area of corporate strategy, treasury, operations management, information technology and market survey. A consultant may also be engaged when financial institutions lack the necessary capacity or resources for a specific project to implement new business processes. On the other hand, an adjuster is defined in S.2(1) of the FSA as a person who carries on the business of investigating the cause and circumstances of a loss and ascertaining the quantum of the loss in relation to insurance or takaful claims. Again, permitted disclosure to these outsiders is diluting the bank’s duty of secrecy. However, similar to the rationale of outsourcing, skilled resources are difficult to hire and can have a ripple effect throughout the organisation, limiting agility when responding to emerging trends and consumer demands, and potentially creating compliance and risk vulnerabilities.[40] Thus, it is vital for banks to outsource and engage with professional consultants and adjusters to assist in the management of businesses. Such dilution is thus unavoidable and justifiable. F. Power of Bank Negara Malaysia Apart from the listed categories in Schedule 11, there is another significant exception where disclosure is permitted, that is, where such disclosure is approved in writing by BNM, as per S.134(1)(b). Thus, a banker or its officers can divulge documents or information relating to the affairs or account of its customer upon receiving the written consent of BNM. This would mean that BNM can make the scope of ‘banking secrecy’ as flexible as it wishes. Furthermore, BNM is equipped with another power by S.134(3) to amend or revoke any existing conditions or impose any new conditions at any time in respect of permitted disclosures set out in Schedule 11 or S.134(1)(b). The author recognises that BNM is the regulator of all banks in Malaysia and takes the responsibility to develop a sound, robust, resilient and progressive financial sector. However, the extensive power given to BNM gives rise to a danger that BNM can go further than the common law exceptions and those statutorily provided in Schedule 11. It is the author’s concern that such sweeping power is not justifiable and may defeat the intention of the Parliament by further attenuating a banker’s duty of secrecy than what was originally meant by the legislature when passing the Bill. V. Personal Data Protection Act 2010—A Ticking Time Bomb In the current information age[41] where large quantities of personal information relating to customers are held by banks on their databases, the threat of customer information being hacked by third parties is particularly significant. Malaysia has timely introduced a law relating to personal data protection with the passing of the Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (‘PDPA’).[42] S.14 of the PDPA requires certain classes of data users, including banking and financial institution, to register with the Personal Data Protection Commissioner. Hence, it is crucial to examine the PDPA to see whether it coordinates with the FSA in diluting the banker’s duty of secrecy, despite having always been labelled as a consumer protection legislation.[43] S.5(1) of the PDPA requires the processing of personal data by a data user to comply with the eight personal data protection principles. The relevant principle regarding the dilution of bank’s duty of secrecy would be the disclosure principle under S.8. At first instance, the PDPA seems to strengthen secrecy of customer information. A closer purview of the disclosure principle, however, suggests exactly otherwise. S.8 provides that no personal data can be disclosed without the consent of the data subject, but its application is subject to S.39. It is unfortunate that S.39 provides for wider exceptions to the disclosure of customer’s personal data. While the statutory exceptions in the FSA is, at least to a certain extent, justifiable, its counterpart in PDPA is overreaching and disproportionate:

Even worse, under S.39(e) of the PDPA, disclosure is permitted if it is justified as being in the public’s interest in circumstances determined by the Minister in charge of the protection of personal data. Put simply, the Minister has absolute discretion to determine whether such personal data can be disclosed in the interest of public. The author is concerned that the wide power conferred to the Minister is one step too many and customer information is at risk. VI. CONCLUSION In recent years, the global tide has flowed against having strict secrecy rules. Measures have been taken in many jurisdictions to create new inroads to the duty to combat the scourge of financial crimes and to increase operational efficiency in the banking sector. The author submits that it is a necessity for the many exceptions to the banker’s duty of secrecy to exist in Malaysia as modern banking development requires so. It is recognised that while the duty under the FSA is indeed diluted, it is unassailable to improve overall business performance, achieve process improvisation and eventually enhance customer service. It is also a must to chase away the dark shadow casting over the secrecy regime by its use for money laundering, fiscal offences and other related criminal activities. Therefore, the author is willing to affirm the permitted disclosures set forth in Schedule 11, as it would enable the law of banker’s secrecy to keep pace with developments in the financial sector. These exceptions in the FSA are justifiable and not an adventure too far. Nevertheless, the only black sheep amongst all would be the overreaching exceptions in the PDPA to lift the veil of banking secrecy, and it is high time for the Parliament to review such unsatisfactory law. Fortunately, the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia is in the midst of reviewing the PDPA to ensure it is up-to-date and in line with the current developments.[44] It is hoped that the somewhat open-ended approach for bankers to bypass liability in disclosing customer information can be addressed accordingly. On a final note, it is true that banking secrecy is not an absolute value, but it is still a cornerstone between the bank and customer. The more unreasonable and unjustifiable the erosion of duty is, the more fragile the public confidence in the financial institutions. Thus, in maintaining and further fostering public confidence, the lawmakers of our country must always be sensitive, reserved and meticulous in passing any law that might dilute the banker’s duty of secrecy. Written by Benjamin Kho Jia Yuan, a final year law student of the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya. The author would like to express his sincere gratitude to Mr Wong Sheng Wei and Mr Adam Huang Tung Kai, for their support in the writing of this article. Edited by Jean Lee and Corina Robert. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Malaya Law Review, and the institution it is affiliated with. Footnotes:

[1] Financial Services Act 2013 (Act 758). [2] Bank Negara Malaysia, “Financial Services Act 2013 and Islamic Financial Services Act 2013 Come into Force”, Bank Negara Malaysia—Press Releases, 1 July 2013, 31 Mar. 19 <http://www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?ch=en_press&pg=en_press&ac=607&lang=en>. [3] Islamic Financial Services Act 2013 (Act 759). [4] Tournier v National Provincial and Union Bank of England [1924] 1 KB 461. [5] Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989 (Act 372). [6] Banker’s Books (Evidence) Act 1949 (Act 33). [7] E.P. Ellinger, Eva Lomnicka and Richard Hooley, Ellinger’s Modern Banking Law, 4th ed., (London: Oxford University Press, 2006), at 183. [8] Tan Lay Soon v Kam Mah Theatre Sdn Bhd (Malayan United Finance, Intervener) [1992] 2 MLJ 434. [9] See footnote 7 above, at 188. [10] See footnote 7 above, at 184-194. [11] Badariah Sahamid, “Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorism Financing Act 2001: Impact on the Duty and Liability of Banks”, Inaugural University of Malaya Law Conference (Kuala Lumpur, 29-30 Nov. 2005). [12] Income Tax Act 1967 (Act 53). [13] Capital Markets and Services Act 2007 (Act 671). [14] Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Act 2009 (Act 694). [15] Anti-Money Laundering, Anti-Terrorism Financing and Proceeds of Unlawful Activities Act 2001 (Act 613). [16] Salleh Buang, “AMLA: An extremely powerful legislation”, New Straits Times, 26 July 2018, 14 Dec. 2018 <https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/columnists/2018/07/394517/amla-extremely-powerful-legislation>. [17] Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 (Act 234). [18] Customs Act 1967 (Act 235). [19] Copyright Act 1987 (Act 332). [20] Child Act 2001 (Act 611). [21] Anti-Trafficking in Persons and Anti-Smuggling of Migrants Act 2007 (Act 670). [22] International Trade in Endangered Species Act 2008 (Act 686). [23] Wildlife Conservation Act 2010 (Act 716). [24] A. Rahman Aspalella, “Combating money laundering and the future of banking secrecy laws in Malaysia", Journal of Money Laundering Control”, (2014) 17(2) Journal of Money Laundering Control 219-229, at 221. [25] Credit Reporting Agencies Act 2010 (Act 710). [26] P. Aruna, “Clearing misconceptions about credit reporting agencies”, The Star Online, 5 Sep. 2017, 13 Dec. 2018 <https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2017/09/05/clearing-misconceptions-about-ctos/>. [27] Turner v Royal Bank of Scotland plc [1999] 2 All ER (Comm) 664. [28] David Dass, et al., “The Credit Reporting Agencies Act 2010 (Part 1)”, Online posting, 26 Oct. 2010, Christopher Lee & Co Articles, 15 Dec. 2018 <http://www.christopherleeco.com/wp3/?p=728>. [29] Mariette Peters-Goh and Amylia Soraya Aminuddin, “The Malaysian Credit Reporting Agencies Act comes into force”, Online posting, 19 Nov. 2014, Zul Rafique & Partners Articles, 15 Dec. 2018 <http://www.inhousecommunity.com/article/the-malaysian-credit-reporting-agencies-act-comes-into-force/>. [30] E.P. Ellinger, E. Lomnicka and C. Hare, Ellinger’s Modern Banking Law, 5th ed., (London: Oxford University Press, 2011), at 194. [31] See footnote 30 above. [32] Saloman v A Saloman & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22. [33] Bank Negara Malaysia, Management of Customer Information and Permitted Disclosures, 17 Oct. 2017, 15 Dec. 2018 <http://www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?ch=57&pg=146&ac=633&bb=file>, at 20-21. [34] Bernama, “BNM issues policy document on outsourcing”, Malay Mail, 28 Dec. 2018, 31 Mar. 2019 <https://www.malaymail.com/news/money/2018/12/28/bnm-issues-policy-document-on-outsourcing/1707141>. [35] Bank Negara Malaysia, Outsourcing - BNM/RH/PD 028-93, 28 Dec. 2018, 31 Mar. 2019 <http://www.bnm.gov.my/index.php?ch=57&pg=146&ac=633&bb=file>, at Paragraph 5.2 [36] Donaldson, Aaron and George Simms, “How financial institutions can gain efficiencies through outsourcing”, Online posting, 2 Oct. 2017, RSM US LLP, 15 Dec. 2018 <https://rsmus.com/what-we-do/industries/financial-services/banking-and-capital-markets/financial-institutions/how-financial-institutions-can-gain-efficiencies-through-outsour.html>. [37] LP Baldwin, Z Irani and PED Love, “Outsourcing information systems: drawing lessons from a banking case study”, (2001) 10 European Journal of Information Systems 15-24, at 23. [38] See footnote 35 above, at Paragraph 9.9. [39] See footnote 33 above, at 19. [40] See footnote 36 above. [41] ‘Information age’ is defined as the modern age regarded as a time in which information has become a commodity that is quickly and widely disseminated and easily available especially through the use of computer technology - Information age [Def. 1], Merriam-Webster Online, retrieved 13 Apr. 2019 <https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Information%20Age>. [42] Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (Act 709). [43] Putik Ladaby and Edwin Lee Yong Chieh, “More protection for consumers”, The Star Online, 28 Oct. 2010, 6 July 2019 <https://www.thestar.com.my/opinion/columnists/putik-lada/2010/10/28/more-protection-for-consumers/>. [44] Bernama, “Gobind: Personal data protection law being reviewed”, The Star Online, 18 Mar. 2019, 14 Apr. 2019 <https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/03/18/gobind-personal-data-protection-law-being-reviewed/#f1fzOXMie8LbyUhK.99>.

2 Comments

13/11/2019 04:29:40 pm

I don't live in Malaysia, that's why I am not familiar with the laws they have in their, especially those laws that were especially made because they feel that the people might need it. In regards with the tax problems, that is something that I am not familiar of. It has always been a topic that I find really complicated that's why I don't try to touch it as much as possible. But still, I am glad and grateful that I got the chance to see this article that you wrote.

Reply

30/5/2020 06:34:08 pm

It is frightening when every month one has to face the sky rocketing bills of their unsecured debts. The debt relief is the only thing that comes in your mind when you really have to struggle for the minimum payments of your bills. Most people in desperation are attracted to one of the commercial for immediate debt relief and invite a more serious financial trouble.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

CategoriesAll Comments Criminal Law Environmental Law Law And Society UMLR |

|

|

PhoneTel : +603-7967 6511/6512

Fax : +603-7957 3239 |