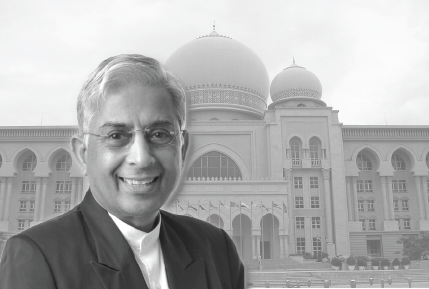

|

Professor Emeritus Datuk Dr Shad Saleem Faruqi is the holder of the Tunku Abdul Rahman Foundation Chair I. CONCEPT OF A LEGAL SYSTEM A legal system refers to the overall legal regime of a country. It provides institutions, principles, rules and methods for regulating the relationship between law and society. It describes law’s connection with authority and with morality. It describes the sources from which the law springs. It provides the procedures and methods for making law and resolving disputes. It encompasses the institutions, principles and procedures for the exercise of power and the limits thereon. It includes a set of laws and the manner in which the laws are interpreted and enforced. It outlines the rights, responsibilities, and duties of citizens towards each other and towards the state. It provides for the imposition of punishments. It provides for the classification of laws into various categories (civil law and criminal law, public law and private law, procedural law and substantive law, the law of tort and law of contract) and the differences and similarities between these categories. Over the millennium, the world has known many types of legal systems. The oldest were built on custom and religion. In modern times, it is believed that there are six primary categories of legal systems; civil law systems, common law systems, religious systems, customary systems and supranational systems, and mixtures of the five. The choice of one or the other is affected by history, politics, and social traditions. A. Civil Law Systems In civil law systems, the central source of law is an enacted Constitution and a plethora of comprehensive Codes passed by legislatures or other law-giving authorities. For example, the Hammurabi’s Code in ancient Babylon (1745-1702BC) and Code Napoleon (1804). Only legislative enactments (and not judicial precedents as in common law systems) are considered legally binding. Legislators play a central role in the development of the law. A significant feature of this system is the extensive codification and consolidation. Another significant feature is that court proceedings are inquisitorial instead of adversarial. Judges conduct investigations, and call and question witnesses. B. Common Law Systems This is a system in which the seminal or primary source is the authoritative decisions by judges in cases that are litigated before the courts. Court proceedings follow the adversarial system of justice. The decisions are perpetuated by a system of binding judicial precedent or stare decisis. Alongside judicial precedents, stand statutes passed by the legislature. However, the relationship between courts and the legislature is complex. Courts interpret statutes, often very creatively, and to understand the law one has to supplement legislation with case studies. Often, the law is what the courts say it is! The American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes once said that “the prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law”. In some common law countries like the USA[1], India, Malaysia[2], and Australia the superior courts have the power to review the constitutionality of legislative enactments. Even constitutional amendments passed in accordance with constitutional procedures can be declared beyond the power of Parliament if the amendments destroy the “basic structure” of the Constitution.[3] Recently in Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd[4] a unanimous Federal Court Bench held that the 1988 constitutional amendment to Article 121(1) cannot take away the sacrosanct constitutional principles of separation of powers and judicial independence. C. Religious Systems In these systems, the religious law is the highest law of the land and is interpreted, not by ordinary judges, but by judges of religious or ecclesiastical courts and scholars with prescribed religious qualifications. As the ultimate law is believed to be from a divine source, it is unalterable and beyond the reach of any democratic legislature. The most common religious system in the world today is the Islamic legal system of syariah. The syariah refers (i) to the Holy Qur’an (ii) the Sunnah and Hadith (the practices and sayings of the Holy Prophet) and (iii) the fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence of the jurists). Syariah is based on both divine law (derived from the Qur'an, Sunnah and Hadith), and the rulings of ulama (jurists). An ulamauses the methods of ijma (consensus), qiyas (analogical deduction), ijtihad (research), and urf (common practice) to derive a fatwā (legal opinion). An ulama is generally required to qualify for an ijazah (legal doctorate) at a Madrasa (law school/college) before he could issue a fatwā. During the Islamic Golden Age, classical Islamic law had wide influence and contributed greatly to the development of common law and several civil law institutions.[5] In the 21st century, syariah law governs a number of Islamic countries including Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Iran. Most Muslim countries use syariah only as a supplement to national law in some specified fields primarily of personal law. In Malaysia, the original scheme of things in 1957 was to apply the syariah (i) to only 24 topics of Muslim personal law and some minor crimes not covered by the federal Penal Code, and (ii) to restrict its application to only those professing the religion of Islam.[6] However, since the eighties, due to the policy of Islamisation, the reach of syariah laws is being expanded through legislation as well as judicial decisions to other areas of law like constitutional law, commercial law, banking, insurance, provident funds, and family law. Conflict of law situations are now endemic. D. Customary Legal Systems In many African nations, legal systems are grounded in customary law which reflects the traditional cultural values. E. Supranational Legal Systems In many European states, supranational regional legal systems have developed. Britain, France, most other Western and some Eastern European countries now fall under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (the ECJ in Luxembourg) which deals with common economic issues. There is also the European Court of Human Rights (the ECHR in Strasbourg in France).[7] II. MALAYSIA – ITS GEOGRAPHY, HISTORY AND PEOPLE A. Geography Geographically, Malaysia consists of two non-contiguous regions; Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia. These two regions are separated by 1,200 kms of the South China Sea. Peninsular Malaysia was formerly called the Federation of Malaya. It consists of 11 states plus the two federal territories of Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya. Together they comprise only 132,090 sq kms or 39.7% of Malaysian territory, but are home to 79% of the population. East Malaysia consists of the two Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak, plus the federal territory of Labuan. The three regions comprise 198,847 sq kms or 60.3% of Malaysian territory, but have only 21% of the population. The 2017 population of Malaysia is estimated to be about 31.5 million. B. History of Malaya In the mists of distant time, Malaya was inhabited by the ancestors of Negritoes and Senoi, the Proto-Malays from South China and the Deutro Malays from Yunnan in South West China. From the beginning of the first to the thirteenth century, migration from India resulted in the establishment of several Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms in Indo-China. The Buddhist Kingdom of Sri Vijaya in Sumatra around the seventh century and the Javanese kingdom of Majapahit in Sumatra in the fourteenth century are well known.[8] Muslim traders from India and the Arab peninsula introduced the Malays to Islam in the fourteenth century. In the fifteenth century, a prince from Palembang, Parameswara, took refuge in Malacca and established the Malacca Sultanate. His conversion to the Islamic faith provided the impetus for the Islamisation of the entire peninsula and the gradual replacement of indigenous animistic practices and Hindu and Buddhist tenets with Islamic principles. The patriarchal adat temenggong easily absorbed principles of Islamic law. The legal system, however, continued to exhibit the richness and diversity of animistic traditions, Malay adat, Hindu and Buddhist feudal and princely traditions, and Islamic tenets. By the time the Portuguese colonialists arrived in 1511, Islam had become the identifying feature of Malay society. A remarkable development during the reign of Sultan Muzaffar Shah (1444-1456) was that orders were issued to compile laws into Hukum Kanun for the sake of promoting uniformity of justice. Between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries, Digests and Codes were compiled – among them were the Undang-Undang Melaka (Risalut Hukum Kanun 1523), Undang Laut Melaka, Pahang Digest 1596, Kedah Digest 1605, Johor Digest, and the Ninety Nine Laws of Perak. From 1511 onward, Malaya was colonised by the Portuguese (1511-1641); the Dutch (1641-1786); and the British (1786-1957). The 171 years of British colonial rule are especially significant. The colonial period reshaped Malayan legal traditions and supplied a large corpus of statutory and common law to replace Malay customs and Islamic law that were prevalent in Malaya before the advent of the British. Opinions vary on the legacy of the British to the legal system of Malaysia[9] but what is certain is that British influence – both good and bad – is still felt 60 years after Merdeka. C. History of Borneo States The regions of (North Borneo) Sabah and Sarawak have their own distinct ancestry and history. They were populated by Dayaks; descendants of the proto-Malays who had migrated across the Malay peninsula between 2500 and 1500 BC. There were also the Bataks of Sumatra, Negritoes or Senoi, deutro-Malays from the peninsula, and the Chinese around the fifteenth century.[10] By the sixteenth century, the Borneo territories were under the sovereignty of the Sultan of Brunei. In 1841, Raja Muda Hashim, in exchange for assistance to suppress an uprising, installed British trader James Brooke as the Governor of Sarawak. This ushered the era of British colonialism through the White Rajahs – James Brooke 1841-1868, Charles Brooke 1868-1917, and Vyner Brooke 1917-1941. In 1847, Labuan was ceded to the British. James Brooke was appointed as the British Consul-General for Brunei and Borneo. The British North Borneo Company was formed by the Royal Charter in 1882. In 1888, Britain declared Brunei, Sabah, and Sarawak to be protectorates. Though the Codes of Law and the Royal Charters were enacted, indigenous customs, native law and matters of religion were left untouched. British law was introduced only in 1928 through the Law of Sarawak Order.[11] The British ruled North Borneo (Sabah) and Sarawak for 123 years till 1963. D. Merdeka for Malaya The 11 states of the Malay Peninsula were under British rule till Malaya’s independence on August 31, 1957. A new and supreme Constitution drafted by the British-led Reid Commission was launched at midnight on August 31, 1957 when Malaya met its tryst with destiny. E. From Malaya to Malaysia In 1963, the Federation of Malaya joined the British territories of Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore to create a vastly enlarged federation with a new name “the Federation of Malaysia”. However, the Constitution of 1957 was retained but with eighty or so amendments to accommodate the special autonomy of Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore. F. Exclusion of Singapore In 1965, the Constitution was again amended significantly to allow Singapore to leave the Federation to become an independent, sovereign state. G. Culture Malaysia is a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, multi-linguistic and multi-religious society and its legal system reflects its cultural diversity and its colonial history. H. Language Malay language is the official language under Article 152. However, subject to some limitations, the teaching, learning and use of other languages are allowed in all educational institutions whether public or private and at all levels.[12] Languages other than Malay may be used for non-official purposes. I. Islam Islam is recognised by Article 3 of the Constitution as the official religion, but other religions may be practised in peace and harmony. The religious breakdown of the population is 61.3% Muslim; 19.8% Buddhist; 9.2% Christian; 6.3% Hindu; 1.3% Confucianism, Taoism and other Chinese faiths; 1.4% other religions and 0.7% no religion. J. Ethnic Composition Ethnically, Malays constitute 55% of the population; Sabah and Sarawak indigenous people (“Bumiputeras”) constitute 14%; Chinese 23%; Indians 7% and Others 1%. III. PROMINENT FEATURES, PRINCIPLES AND LAWS OF THE MALAYSIAN LEGAL SYSTEM A. Legal Pluralism The Malaysian legal system consists primarily of secular Codes drafted by legislative authorities. However, there are syariah laws for Muslims in 24 or so personal law matters enumerated in the Constitution. In addition, the customs of the Malays and the people of Sabah and Sarawak are part of our law. At one time, the Chinese and Hindu customs were recognised in family law relations. However, due to the passage of the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976, family law for non-Muslims has now been codified. There is legal pluralism in that there are different systems of law and different systems of courts which operate within their assigned spheres. We have a hierarchy of civil courts, a different hierarchy of syariah courts, and another hierarchy of native courts in Sabah and Sarawak. Unfortunately, conflict of laws between civil courts and syariah courts in West Malaysia, and native courts and syariah courts in Sabah and Sarawak is endemic and increasingly, the various streams of law compete with each other for ascendency. B. Written and Supreme Federal Constitution We have written constitutions at the federal level as well as in all 13 states. The Federal Constitution is supreme throughout the land. It is declared in Article 4(1) that this Constitution is the supreme law of the Federation and any law passed after Merdeka Day which is inconsistent with this Constitution shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void.[13] The State Constitutions are supreme in the respective states but subject to the primacy of the Federal Constitution in the sense that all State Constitutions must contain some “essential provisions” prescribed by the Federal Constitution.[14] C. Judicial Review The supremacy of our Constitution is supported by judicial review. The Constitution in Articles 4(1), 4(3), 4(4), 128(1), and 128(2) is explicit about the power of the superior courts to examine the constitutionality of all executive[15] and legislative actions. As in many other countries, Malaysian courts are reluctant to employ the instrument of unconstitutionality to dissect state actions. Nevertheless, a fair amount of case laws has developed on constitutional challenges in the area of federal-state division of powers;[16] unlawful interference with fundamental rights;[17] violation of constitutional amendment procedures;[18] abuse of emergency powers;[19] and the Attorney-General’s exclusive power under Article 145 to commence prosecutions.[20] D. Islam as the Official Religion Article 3(1) declares Islam to be the religion of the Federation. However, there are protections for believers of all other faiths as follows;

Muslims are, however, compulsorily subjected to the syariah and to the jurisdiction of the syariah courts. The syariah law that is applicable in Malaysia is largely of the Shafie school of Islam with influences of the Malay adat. The formulation of Islamic Law Enactments is largely left in the hands of the State Assemblies, each of which enacts laws for its territory. The three federal territories of Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya and Labuan have a separate Act applicable to them. It must be noted that though Islam is the religion of the Federation, Malaysia is not a theocratic, Islamic state. The Federal Constitution is the highest law. Islamic law applies compulsorily to all Muslims but only in 24 areas (primarily of family law) enumerated in Schedule 9 List II Para 1. In all other areas like crime, contract and tort, Muslims are governed by secular laws enacted by elected assemblies. However, since the eighties, a policy of Islamisation is in effect and some areas of federal legislation (like banking, insurance, loans) are being influenced by syariah principles that are being posited into legislation applicable to all persons. There is increasing assertiveness by the syariah establishment in many areas of social life that affect Muslims[21] as well as non-Muslims.[22] Some very painful and intractable conflict of jurisdiction cases between civil and syariah courts remain unresolved.[23] E. Federal System Malaysia has a federal system of government but with a heavy central bias. However, the East Malaysian regions of Sabah and Sarawak enjoy some executive, legislative, judicial and financial autonomy not available to the 11 Peninsular states. This asymmetrical arrangement for special treatment is entrenched in the 1963 amendments to the Constitution.[24] F. Constitutional Monarchy We have a constitutional monarchy at both the federal and state levels. The unique aspects are that (i) we have not one but nine Rulers – one at the federal level and nine hereditary Sultans/Rajas at the state levels while four states without hereditary rulers have State Governors, and (ii) the federal monarchy is elected and rotational. The King is elected by his nine brother Rulers for a period of five years. G. Democratic System The Malaysian legal system has most of the formal attributes of a democracy – elections to choose the federal and state governments; a bicameral Parliament at the federal level; a unicameral Assembly in each of the States; a well-developed electoral system; a system of political parties; a judiciary with safeguards for judicial independence; and constitutional protection for enumerated human rights in Article 5-13. But unfortunately, there are also constitutional permission for executive detention without trial, laws about sedition, treason, official secrets, prior restraints on free speech through licensing and permits for the media, police control over assemblies and processions and censorship and banning of books and publications. H. Parliamentary System We emulated the British, Westminster style of parliamentary government at both federal and state levels. I. Electoral System The Constitution and laws provide for the main electoral principles. We have a single member constituency system. Every citizen of age 21 who has registered as a voter in a constituency is eligible to vote unless he or she suffers from an electoral disqualification. Right to seek elected office is likewise protected and no racial, religious, gender, educational or income criteria apply. Victory in a constituency is on a “simple plurality” vote and there is no proportional representation. There are no reserved seats for the army,[25] police or any race or religion in the elected House of Representatives. The federal Senate is, however, mostly appointed. It has 44 appointed members and 26 indirectly elected Senators – two from each State indirectly elected by the 13 State Assemblies. Regrettably, Malaysia has no local authority elections though these did exist in the early years of independence. J. Fundamental Rights The Federal Constitution in Article 5-13 confers a number of civil and political liberties. Among them are;

Elsewhere in the Constitution, there is a right to vote (Article 119), right to seek elective office (Articles 116-117), protection for public servants (Articles 135 and 147), and some protection for preventive detainees (Article 151). A number of ordinary statutes confer rights to the women, children, workers, pensioners, consumers, trade unionists etc. K. Access to the Courts In theory, the right of access to the courts for the enforcement of rights is regarded by some judges as part of the constitutional guarantee of personal liberty. According to Justice Gopal Sri Ram, JCA as he was then, the right to go to courts is part of the constitutional right to personal liberty. Regrettably, for 70% of the accused in lower courts who are unrepresented, the right of access is unenforceable because of the high cost of litigation and the infancy of legal aid and advice. In Malaysia, lawyers are not allowed to seek contingency fees, give rebates or advertise their services. These rules impact adversely on citizens’ ability to seek legal redress. L. Indigenous Features Though the 1957 Constitution was drafted by a foreign Commission appointed by the British, it worked closely with the then political leaders of Malaya and the multiracial Alliance to incorporate into the basic law some unique and indigenous features of the Malay archipelago. Among them are:

M. Nationality Nationality is not equated with ethnicity but with citizenship and exclusive allegiance. Double citizenship is not allowed. N. No immunity for the Sultans and the Government Most remarkably, the King and the Malay Rulers are subject to the civil and criminal law and can be taken to a special court. The government is not immune from civil proceedings in contract or tort.[26] However, it enjoys some procedural advantages: the time limit in contract and tort to sue the government is reduced from 6 years to 36 months. Evidence may be withheld in the public interest. Facts may be suppressed under the Official Secrets Act. Some remedies like injunction and specific performance are not available against the government. In some situations, the government may even have total immunity. O. Civilian Control over the Forces Even during the communist insurgency (1957-1989) or during racial riots in 1969 or during the emergency (1964-2012), there has been civilian control over the army and the police. We have had no coup d’etats or “stern warnings” from the armed forces. Separation of the police force from the armed forces, and a parity between the top echelons of the army and the police achieve an admirable check and balance between the two. P. Branches of Law Almost all branches of law have developed in Malaysia. There are statutory codes on court procedure and evidence; cyber laws; human rights; children’s protection; protection for women; personal and family laws; labour relations and workers’ rights; banking, commercial relations, contract, sale of goods, hire purchase; environmental protection; intellectual property; official secrets; whistle blowers’ protection; laws relating to land and tenancies and; laws to regulate education. Laws on international trade and commerce are gaining foothold. Q. Various Classifications of Laws Legal rules are of many types. They may be classifiable in a number of classes which are not watertight. Such classification has distinct consequences not all of which are desirable. Such classifications are;

IV. SOURCES OF LAW A. Concept of Law in Legal Philosophy Law is an indispensable attribute of every society- ancient or modern. Law has existed since times immemorial in myriad of forms. There is no universal concept of law. There are many competing conceptions. Much depends on your upbringing, pre-conceptions and political and legal philosophy. An all-encompassing definition is not possible. But if we were forced to supply one, we could say that law is “a norm or rule of conduct”. The problem is that rules of conduct exist in many forms and originate from a myriad of sources.

Which of the above sources or forms of law qualify as legal sources? There is no right answer. Much depends on whether you belong to the historical and anthropological, natural law, legal positivist, sociological, realist or post-modernist approach. B. Malaysian Concept of Law In Malaysia, Article 160(2) of the Federal Constitution supplies an authoritative definition of law. It states that “law” includes written law, the common law in so far as it is in operation in the Federation or any part thereof, and any custom or usage having the force of law in the Federation or any part thereof. From the above definition, it is clear that at least three categories of rules qualify as law in this country: 1. Written law This category includes the Federal Constitution, Acts of the Federal Parliament, Emergency Ordinances by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong under Article 150, Federal Subsidiary Legislation, 13 State Constitutions, Enactments and Ordinances of State Assemblies, State Subsidiary Legislation and local authority by-laws. In the context of Sabah and Sarawak, British statutes at cut off dates may be applied as law if there is no local legislation. In the field of commercial law, British statutes at cut off dates may be applied throughout the country if there is no local legislation. 2. English common law and Malaysian judicial precedents Unlike in the civil law system, judicial precedents formulated by Malaysian and UK judges in the course of deciding cases have the force of law, and are honoured by a system of stare decisis. 3. Customs or usages These become law if they are recognised by statute or common law. It is noteworthy that under Article 160(2) religion, ethics, morality and custom are not law per se on their own strength or quality. Neither is there legal recognition for social practices, rules of international law and private law unless these are incorporated into or derived from a recognised source of law. Our legal system does not address the question whether an unjust law (“a lawless law”) is law. However, religion, ethics, morality, custom, social practices, rules of international law and private law may be admitted into law in two ways: (i) by incorporation, adoption or being posited into a written statute or; (ii) by acceptance into a judicial precedent. This narrow, unhistorical and amoral (morally neutral) approach to the definition of law indicates that in Malaysia the English philosophy of “legal positivism” is the preferred approach. Law is a command of the sovereign. Law is state-made. Its morality or immorality, its reasonableness or justice are irrelevant in determining its validity. Besides state-made law, other types of rules or norms need direct or indirect recognition by the state or it agencies before they can acquire the status of law and enforceability as a legal norm. This means that only those rules of social and legal practice are enforceable in a court which have passed through a “legal filter”, a “rule of recognition” or a “criterion of validity”.[27] In practice, statutory recognition of custom or religious precepts is quite frequent. In West Malaysia, it is quite common to see Muslim family law statutes containing a clause to the effect that “the law on this point shall be the law of the Syafie school of Islam and Malay adat”. In Sabah and Sarawak, a great deal of native custom is codified. Though judicial practice is not always consistent, there is no dearth of cases in which judges give judicial recognition to Malay and Chinese customs and native law in Sabah and Sarawak. Since the nineties, superior courts are increasingly incorporating principles of Islamic jurisprudence into their judicial decisions. C. Meaning of ‘Sources’ The term “sources of law” can have many meanings. One meaning is “historical sources” or “material sources”. These terms refer to the fountains from which the content of the law is derived. Everywhere in the world, some parts of the legal system are inspired by and based on cultural, moral, religious or customary norms, scholarly opinions or the edicts of religious or customary authorities. These norms supply the lifeblood of the law; the clay from which law is fashioned. However, in legal systems influenced by the approach of legal positivism, these historical or material sources are not, by themselves, entitled to be called “law” unless they are formally posited or converted into law by legislation or judicial precedent. Another meaning of “source” is the institutions or authorities that are authorized by a particular legal system as having the power to enact law. Thus, Parliament and State assemblies are the source of legislation. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong is the source of Emergency Ordinances; and courts are the source of common law. The third meaning of “source” is those formal categories or species of rules that are recognized in the legal system as constituting the law of the land. D. Sources of Law in Malaysia The Federal Constitution in Article 160(2) defines ‘law’ to include three sources:(i) written law, (ii) the common law and (iii) any custom having the force of law. This means that legislation, subsidiary legislation, judicial precedents and recognized customs are the “source of law” in Malaysia. Under the Civil Law Act 1956, British common law and equity on particular cut-off dates are statutorily recognised as sources of law. Under the Civil Law Act, British statutes in the field of commercial law on cut-off dates are applicable throughout Malaysia if suitable to our circumstances. Also, British statutes of general application on cut-off dates, if suitable for Sabah and Sarawak, are applicable in Sabah and Sarawak. Under Article 162(6), “existing laws” of the pre-independence era may continue to exist but subject to modification to make them fall in line with the supreme Constitution. The effect of the above provisions is that there are multiple sources of law in Malaysia. They can be divisible broadly into: (i) written sources and (ii) unwritten sources. 1. Written sources “Written” means formally “enacted” into legislation or subsidiary legislation. Written does not mean “in print” or in black and white. The written sources at the federal level are:

At the state level, the written sources are: 1. The thirteen State Constitutions; 2. State Enactments (in Sarawak, Ordinances) under Articles 73, 74, 76A and 77 of the Federal Constitution or under the enabling provisions of their own State Constitutions; 3. State subsidiary legislation including municipal by-laws; and 4. In the context of Sabah and Sarawak, British statutes of general application at cut-off dates may be applied if there is no local legislation and if the law is suitable to our circumstances. (a) Federal Constitution The Federal Constitution is the supreme law of the land, the law of laws- the grundnorm. It sits at the apex of our legal hierarchy. What was achieved by Marbury v Madison[28] in the USA is explicitly provided for in Articles 4, 128 and 162(6) of Malaysia’s Federal Constitution. Any law, whether post-Merdeka or pre-Merdeka, primary or secondary, federal or state, secular or religious, that violates the Constitution can be declared null and void by the courts. The supremacy of our Constitution is supported by judicial review. The Constitution in Articles 4(1), 4(3), 4(4), 128(1) and 128(2) is explicit about the power of the superior courts to examine the constitutionality of all executive[29] and legislative actions. As in many other countries, Malaysian courts are reluctant to employ the instrument of unconstitutionality to dissect state actions. Nevertheless, a fair amount of case laws has developed on constitutional challenges. In the area of federal-state division of powers, we have The Government of Kelantan[30]; The City Council of George Town[31]; Government of Malaysia[32]; Mamat Daud[33]; Abdul Karim Abdul Ghani[34]; Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Alam Sekitar[35]; Robert Linggi[36]; Dato’ Ting Cheuk Sii[37] ; and Fung Fon Chen@ Bernard.[38] In relation to unlawful interference with fundamental rights, there are hundreds of applications to the courts. Some of the prominent ones are PP v Yee Kim Seng[39]; Che Ani Itam v PP[40]; Tye Ten Phin[41]; Pihak Berkuasa Negeri Sabah[42]; Yii Hung Siong v PP[43]; Ooi Kean Thong v PP[44]; Muhammad Hilman Idham[45]; Fathul Bari Mat Jahya[46]; Nik Noorhafizi Nik Ibrahim v PP[47]; Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad v PP[48]; Berjaya Books[49]; Mat Shuhaimi Shafiei v PP[50]; Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur[51]; PP v Azmi Sharom[52]; State Government of Negeri Sembilan[53]; PP v Yuneswaran Ramaraj[54]; Pathmanathan Krishnan[55]; ZI Publications[56]; Majlis Agama Islam WP[57]; Maria Chin Abdullah lwn Pedakwa raya[58]; YB Khalid Abdul Samad[59]; and Khairuddin Abu Hassan[60]. On the violation of constitutional amendment procedure, there are cases like The Government of Kelantan[61] and Robert Linggi[62]. On the exercise or abuse of emergency powers we have Teh Cheng Poh v P [63] and Abdul Ghani Ali @ Ahmad v PP[64]. On the Attorney-General’s exclusive power under Article 145 to commence prosecutions, we have a dozen or so cases including Subramaniam Gopal v PP[65]. Despite the above cases, one can say regrettably, that 60 years after independence the Constitution has not yet become the chart and compass, the sail and anchor of the nation’s legal endeavours. Its imperatives have not become the aspirations of the people or the institutions of the state.

(b) Federal legislation by the elected parliament There are nearly one thousand federal statutes on record. They are called Acts of Parliament or statutes. All are printed in the Government Gazette and are accessible without cost to anyone who cares to obtain them. The Government claims no copyright to its legislation. Interpretation Acts supply a guide to statutory interpretation. The relevant laws are the Interpretation and General Clauses Ordinance 1948 applied for the interpretation of the Constitution and the Interpretation Acts 1948 and 1967 (Act 388). Though there is widespread codification, there is overlapping legislation and consolidation is an unmet need. (c) Emergency ordinances by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong The King, acting on advice, possesses the power to promulgate Emergency Ordinances having the force of law (i) during an emergency and (ii) if both Houses are not in session concurrently. The power of the King is co-terminus with that of Parliament. (d) Federal delegated (subsidiary) legislation It exceeds parliamentary legislation by a ratio of 1:20. Regrettably, it is not subject to much parliamentary control. In many countries, delegated legislation is statutorily made subject to:

Regrettably, in Malaysia, consultation and laying are very rare. Scrutiny committees are unknown in Malaysian legislatures.[67] However, subsidiary legislation, both federal and state, is subject to judicial review on the principles of unconstitutionality, ultra vires and unreasonableness.[68] (e) British commercial statutes Under the Civil Law Act 1956, section 5(1), English commercial law as it stood on 7 April 1956 applies in the nine former Malay states. Under section 5(2) which applies to Penang, Melaka, Sabah and Sarawak, English commercial law at the date at which the matter has to be decided applies. The qualification is that there must be no local legislation on the point. (f) Pre-Merdeka laws Article 162 specifically provides that all existing laws on Merdeka Day shall continue to be applied until repealed. But any court applying them may apply them with such modification as may be necessary to bring them into accord with the Constitution. “Modification” includes amendment, adaptation and repeal.[69] (g) Thirteen State Constitutions Each of the 13 States has its own Constitution which is required by Article 71 and the Eighth Schedule to contain some “essential provisions” prescribed by the Federal Constitution. These essential provisions are that the Ruler must act on advice; there must be provisions for an Executive Council; and an elected legislature with powers and procedures for enacting laws. (h) State enactments These Enactments can be made on any areas assigned to the State Legislature under Schedule 9, Lists II and III. The State Assemblies of Sabah and Sarawak have additional powers under Lists IIA and IIIA. (i) State delegated (subsidiary) legislation State Enactments may delegate power to any state institution including local authorities and religious officials and committees to enact subsidiary legislation. (j) British statutes of general application Under section 3(1), statutes of general application on particular cut-off dates may apply in Sabah and in Sarawak if there is no local legislation on point. For Sabah the date is December 1, 1951; for Sarawak the date is December 12, 1949. 2. Unwritten sources These are all of non-statutory origin. They are divisible into legal and non-legal sources.

(a) Unwritten legal sources (i) British common law and equity The Constitution recognises common law as a source of law. Under the Civil Law Act 1956, the term ‘common law’ means British common law and equity subject to (i) cut-off dates and (ii) a local circumstances proviso. The cut off dates are 7 April 1956 in West Malaysia;1 December 1951 in Sabah; and 12 December 1949 in Sarawak. These dates reflect the pre-independence incorporation by the British of their legislation into the colonial territories of Malaya, Sabah (North Borneo) and Sarawak. Many other Malaysian statutes, like the Contracts Act, permit our courts to take note of equitable considerations. The Civil Law Act 1956 is subject to tremendous criticisms. First, some say that the umbilical cord that bound us to Britain in 1957 is not necessary 60 years after the growth and development of our own legal system. Second, it is improper to set different cut-off dates (Sarawak 1949; Sabah 1951 and Malaya 1956) for our three different regions. Third, it is silly that ancient and not contemporary English common law is applicable in Malaysia. English common law has developed by leaps and bounds since the fifties. Fourth, why should England have the monopoly of influencing our jurisprudence? In constitutional law, for example, Britain offers no help due to its unwritten Constitution while the Indian and Australian jurisprudence would be much more relevant. For the above reasons, arguments are periodically raised that the Civil Law Act should be amended or repealed and Malaysian courts should develop their own common law. In many areas that is, without doubt, already taking place. This is because the Civil Law Act itself wisely permits Malaysian courts to accept or reject British common law and equity by taking into consideration local circumstances. (ii) Precedents of Malaysian superior courts On the lines of the English legal system, Malaysia follows the doctrine of binding judicial precedent. Traditionally the doctrine applied vertically as well as horizontally. The Federal Court: The decisions of Federal Court bind all other courts in the country. But as an apex court, the Federal Court has the power to overrule its own previous decisions. In the interest of certainty, this power is exercised sparingly. The Federal Court has the power to overrule all other courts and this it does quite often. Court of Appeal: The Court of Appeal is bound by the Federal Court but all other courts are bound by the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal generally follows its own decisions but has the power, without overruling it, “to depart” from its previous precedents.[70] It can overrule the High Courts. High Courts: The two High Courts are bound by the Federal Court and the Court of Appeal, but all inferior courts and tribunals are bound by the High Courts. The High Courts generally follow decisions of other High Courts but have the power, without overruling it, “to depart” from a previous precedent of the High Court. It can overrule the inferior courts on appeal as well on review. Previous courts: It is noteworthy that the judicial decisions of superseded superior courts like the Supreme Court, the former Federal Court and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council continue to have legal status and protection of the doctrine of binding judicial precedent. The Special Court under Article 182: This court has the exclusive jurisdiction to try all offences committed by the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (YDPA) and the Rulers of the States. It also has the exclusive jurisdiction in all civil actions by or against the YDPA and the Rulers in their personal capacity. It is not clear whether the doctrine of stare decisis applies to the Special Court. Under Article 182(5), “the practice and procedure applicable in any proceedings in any inferior court, any High Court and the Federal Court shall apply in any proceedings in the Special Court”. Balance between rigidity and flexibility: Despite the belief that the doctrine of binding judicial precedent stifles judicial creativity, the reality is that it achieves a fine balance between certainty and flexibility.

(b) Unwritten, non-legal sources (i) The syariah The syariah was and is an important part of the Malay identity. In the days of the British, the courts often accepted and occasionally rejected Muslim law in deciding cases.[71] The most prominent cases involving Islamic law were In the Goods of Abdullah[72]; Fatimah & Ors v Logan[73]; Re Maria Huberdina Hertogh[74]; Koh Cheng Seah Administrator of the Estate of Tan Hiok Nee Decd. v Syed Hassan[75]; Ramah binti Taat[76]; Re Ismail Rentah, Decd., Haji Hussain bin Singah v Liah binte Lerang[77]; In re Timah binti Abdullah Decd[78]; Ainan bin Mahmud[79]; Chulas and Kachee[80]; Anchom binte Lampong v PP[81]; In the Matter of Omar bin Shaik Salleh Shaik Salleh[82]; Shaik Abdul Latif v Shaik Elias Bux[83]; PP v D J White @ Abdul Rahman[84]. In the post-independence era, with the adoption of a written Constitution, the legal position of Islamic law is that the principles of the syariah are not law per se under Article 160(2). But State Assemblies are authorized by Schedule 9, List II Para 1 to enact laws on Islam (in 24 areas, mostly of personal law) and on matters of Malay custom. In the era between 1957 and 1988, despite the existence of syariah courts, , the civil courts continued to interpret, apply or dismiss principles of Islamic law in cases before them: Nafisah v Abdul Majid[85]; Martin v Umi Kelsom[86]; AG of Ceylon v Reid[87]; Myriam v Mohamed Ariff[88]; Abdul Rahim v Abdul Haleem[89]; and Re Dato Bentara Luar Dcd., Haji Yahya[90]. However, this reception and adjudication of Islamic law in civil courts came to an end with the constitutional amendment to Article 121 and the addition of Article 121(1A) to the effect that the civil courts “shall have no jurisdiction in respect of any matter within the jurisdiction of the Syariah courts”. Refer to Mansur bin Mat Tahir[91]. Since Mahathir Mohamad and Anwar Ibrahim’s Islamisation policy in the 80s, there has been a steady expansion of the syariah in areas outside family law. Syariah authorities occasionally exercise jurisdiction beyond the 24 areas assigned to them by Schedule 9 List II Para 1. In addition, they violate the chapter on fundamental rights. Judicial review of such excess of power is, however, rather rare. Today, there is talk of an “Islamic state”, “two parallel legal systems”, and “one country with two systems”. The states of Kelantan and Terengganu have even tried but unsuccessfully to legislate hudud laws i.e. criminal laws with penalties prescribed in the Qur’an, Hadith, and the fiqh (jurisprudence) of early Muslim scholars.[92] The legal system is facing intractable disputes between syariah authorities and some Muslims on issues such as Muslim apostasy, cross dressing, freedom of speech, “deviationist teachings” and Islamic education. Constitutional issues are often raised and more often than not rejected by the superior courts. The steady expansion of Islamic laws and the widening jurisdiction of syariah authorities have also brought them in painful disputes with non-Muslims over issues such as the dissolution of a non-Muslim marriage when one partner converts to Islam, the conversion of the children of the marriage into Islam without the consent of the non-converting spouse, and custody and guardianship of the children. Syariah authorities are also flexing their muscles in such matters as use of the term “Allah” by non-Muslims[93], burials of non-Muslims who were suspected by the syariah authorities to have converted to Islam before their death. Islamic law is in resurgence and is often in direct conflict with the constitutional grundnorm. (ii) Malay adat (custom) Before the arrival of the British in 1786, custom was the dominant source of law in Malaya. For the Malay community, custom referred to the composite, indigenous Malay adat enriched by Hindu and Buddhist elements and overlaid with principles of the Syafie school of Islamic law. Though Malay adat (custom) and the Syariah (Islamic law) are distinct, the Malays often see them as synonymous. That is why Malay custom is enforced in syariah courts! Unlike in Sabah and Sarawak, there are no separate adat courts in the peninsula for Malay custom. As colonialism took root, common law became the dominant law of Malaya and Malay adat and Islam were relegated to personal matters, and that too if not repugnant to British notions of natural justice, equity and good conscience. In Sahrip v Mitchell[94], a land tenure case, the Malay custom of tithe or one-tenth of the total produce was accepted as reasonable. In Jainab bt Semah[95], the Malay custom of adoption in Pahang was recognised. However, in Mong binti Haji Abdullah v Daing Mokkah Daing Palamai[96], - a breach of promise to marry case – the court refused to apply Muslim law as that would lead to oppressive results.[97] In post-independence Malaya, Malay customs have constitutional recognition in several articles of the Constitution including Article 150(6A), 160(2) and Schedule 9 List II, Para 1. However, there is no carte blanche recognition of customary law. Under Article 160(2) ‘law’ includes only those customs and usages having the force of law. This means that customs are not law per se. They need the kiss of life from a statute or a judicial precedent. After independence, the role of Islamic law and Malay adat has been gradually enhanced and given statutory basis in the Syariah Enactments of all the states and in some other laws. Custom is occasionally elevated to the status of law by judicial recognition if the custom meets the criteria of morality, reasonableness and justice in the opinion of the court.[98] What standards does the court apply? It is doubtful that 60 years after Merdeka, English standards of reasonableness will apply lock, stock and barrel to customs in Malay society. There is recognition in Khoo Hooi Leong[99] that English law must be applied with modification to alien races. (iii) Native law in Sabah & Sarawak In Sabah and Sarawak, native law and custom have constitutional and statutory recognition as law. For example, the Sarawak Native Court Ordinance 1992 defines customary law as “customs or body of customs to which the law of Sarawak gives effect”. There are many significant cases of native rights to land being litigated in the courts. Decisions have gone both ways, in favour of and against the natives.[100] Native law in family and personal matters is enforced by a hierarchy of Native Courts. But there is no dearth of cases before 1963 and after 1963 when the High Court exercised jurisdiction and gave important decisions on matters of native law: Abdul Latiff Avarathar v Lily Muda[101]; Chan Bee Neo[102]; Kho Leng Guan[103]; SM Mahadir bin Datu Tuanku Mohamad[104]; Serujie & Hanipah[105]; Liu Kui Tze v Lee Shak Lian (f) [1953] SCR 85.[106] The review of native courts’ decisions by the High Court is in contrast with the independence and autonomy of syariah courts under Article 121(1A). (iv)Chinese and Indian customs Malay adat is holding its ground in family and personal law matters, but non-Muslim customs are in decline and have been replaced by secular Codes in independent Malaya. Historically, however, many Chinese and Indian customs were recognized e.g. polygamous Chinese marriages and legitimization of an illegitimate son by a subsequent marriage were recognized in the Matter of Choo Eng Choon, Deceased[107]. Chinese customs were recognized in the distribution of intestate estates: Ong Cheng Neo[108]. Customary Hindu money-lending contracts by the Chettiar community have been recognized by the courts. However, the Chinese custom of legitimization of a natural but illegitimate son was rejected in Khoo Hooi Leong v Khoo Chong Yeok[109] on the ground of morality.[110] (v) Constitutional conventions In the area of constitutional law, hundreds of constitutional customs (called conventions) have developed over the years. For example, there is a daily Question Time in Parliament. During a dissolution of the Dewan Rakyat, the Prime Minister who advises the dissolution stays in office in a caretaker capacity till the new PM and government are inducted into office after the election. As with all customs, these constitutional conventions are not laws and not enforceable in a court of law.[111] They are the political morality of the day. They are the rules of political practice that are regarded as binding by those to whom they apply, but no legal sanction attaches to their disobedience.[112] However, conventions can influence judicial decisions in two ways: first, a court may use a well-established convention as an aid to interpretation of statutory law.[113] Secondly, in some circumstances a court may adopt a constitutional convention as part of his judicial reasoning, thereby elevating the convention to the status of common law.[114] (vi) International law In the definition of ‘law’ in Article 160(2), international law is conspicuously left out. This means that, the norms of international law and practice are not part of our corpus juris unless they are posited into law. This can be done in three ways: First, by statutory incorporation into a local statute. An example is our Human Rights Commission Act which incorporates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into our law subject to the Constitution. Second, international law can be admitted to our shores by our judges by treating it as part of international “custom or usage” which the judges have power to recognize under Article 160(2). Third, it is noteworthy that in the definitional clause in Article 160, the words of the Constitution are “law includes” (and not “law means”). The definition of law is inclusive, not exclusive. The courts have some discretion. Fourth, the courts can adopt a constitutional presumption that, unless the Parliament explicitly excludes international law, the norms of all international laws and treaties ratified by the government must be grafted on to every Malaysian statute even if the Parliament has not adopted international law into local statutes. This is what happened in Noor Fadilla Ahmad Saikin[115] and Lai Meng v Toh Chew Lian.[116] Such a presumption is justified because in this age of globalization, our government must be seen as committed to harmonising its practices and laws with the law of nations. (vii) Quasi-legislation Quasi-legislations by way of Administrative Circulars, Notifications, Instructions, Schemes and Directives do not have the status of law unless framed under the authority of a parent law. In actual practice, these administrative directives are issued regularly and are regarded by the civil service as absolutely binding. Disregarding them can disqualify a citizen from applying for a job, licence, scholarship, loan, passport or permit. Disregard of Government Circulars by a public servant can expose him to internal proceedings for indiscipline though no court case for breach of law can be initiated if the Circular has no legal status and is mere administrative in nature. For a learned judicial decision on the distinction between administrative circulars and subsidiary legislation, see Teh Guat Hong v Perbadanan Tabung Pendidikan Tinggi Nasional[117]. Sources and their hierarchy: A difficult question about the sources of law is whether the 19 multiple sources outlined above exist in a clear hierarchy or as competing streams of law? Theory supports the idea of a hierarchy with the Federal Constitution at the apex. In reality however, the situation is exceedingly complex for many reasons. First, the Constitution is what the judges say it is. For example, Article 5(3) mandates that every arrestee “shall be allowed to consult and be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice”. However, in Ooi Ah Phua[118] the court held that the right can be exercised only after police have completed their investigation. The glittering generalities of Article 5(3) have to be read in the light of judicial precedents which, functionally speaking, become integral parts of the Constitution. Second, the Constitution is often read in the light of other sources of law i.e. legislation, judicial precedents, customs, principles of the syariah and even norms of international practice. A broad, holistic view of the law requires us to see the law as a coordinate whole rather than as separate, hierarchical set of rules. V.PROMINENT INSTITUTIONS Malaysia has a fully developed system of courts, tribunals and dispute resolving and remedial mechanisms. A. Civil Courts At one time, the Privy Council was the highest civil court. In 1985, the Privy Council was abolished. Now we have a court hierarchy headed by:

The first three courts are labelled superior courts and have original, appellate and review jurisdiction. The Federal Court also has advisory jurisdiction. In line with the common law tradition, our legal system is wedded to stare decisis with all its virtues and vices. The highest court (Federal Court) has the freedom to depart from its own previous decisions. Other superior courts (the Court of Appeal and the High Courts) can also refuse to follow their own previous decisions. However, all civil courts (other than the Federal Court) are bound by the decisions of courts above them in the hierarchy. Around the Commonwealth, there are doubts about whether stare decisis should apply rigidly in constitutional and criminal laws matters. It is also notable that this doctrine has no place in the Islamic jurisprudence and in the Europe’s civil law system. B. Syariah Courts Each state creates its own hierarchy of syariah courts. These courts have jurisdiction only over persons professing the religion of Islam. The civil and criminal jurisdiction of Syariah courts is confined to the 24 matters mentioned in Schedule 9 List II, Para 1. Their power to impose punishments is confined to three years’ jail, six strokes of the cane and five thousand ringgit fine (or commonly known as the 3-6-5 formula). This approximately translates to the criminal law powers of Magistrates. In the exercise of their powers the syariah courts are not subject to the control of the civil courts as long as they stay within their jurisdiction under Article 121(1A). The dilemma of the legal system is that the syariah courts often interpret their powers expansively but the civil courts are reluctant to interfere. A most remarkable (or undesirable) feature of the administration of Muslim law in Malaysia is that each state has its own syariah law statute and its own syariah courts. Occasionally, there are serious problems of reciprocal enforcement of judgments. Another remarkable feature of West Malaysian syariah courts is that they enforce not only the syariah but also Malay adat even though in some cases adat and syariah clash. C. Native Courts In Sabah and Sarawak, there is a hierarchy of native courts. An engaging issue in Sabah and Sarawak is that sometimes the Muslim parties are subject to both native law and syariah law and difficult issues arise as to which forum and which law should apply. The State Syariah enactment mandates that if parties are Muslims, the Syariah should apply to the exclusion of native law. In practice, however, many Muslims prefer to submit to the jurisdiction of the Native Courts. D. Tribunals Hundreds of inferior tribunals (known by many names) exist to resolve disputes in such areas as labour disputes, income tax disputes, compulsory land acquisition cases, staff discipline and small claims. These tribunals are less formal than the regular courts, ess expensive and more expeditious. They can be created by statute or be domestic. Whatever their nature is, they are subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the High Court by way of certiorari, prohibition, mandamus, declaration etc. E. Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Techniques Over the last few decades, a host of ADR techniques like Arbitration, Conciliation and Mediation have developed. Regrettably, they are as expensive as the courts. In a third world setting, attention must therefore turn to informal, expeditious and inexpensive remedies like the Ombudsman, Public Complaints Bureau, Letter to the Editor column, Question Time in Parliament, Parliamentary Committee on Complaints to resolve disputes without the hassle of formal judicial proceedings. F. Human Rights Commission We have a statutorily created, independent Human Rights Commission. It issues annual reports and makes recommendations. However, its reports are generally disregarded by the government and parliament. G. Law Reform There is yet no independent Law Reform Commission and the task of reforming the law periodically is handled by a unit in the Attorney-General’s office. H. Elected Legislatures Malaysia practices electoral democracy in that every five years the federal and state governments have to return to the electorate to renew their mandate. Primary laws are enacted by the legislatures, but there is an overwhelming amount of subsidiary legislation and most of it goes uncontrolled. Public participation in the legislative process is insignificant. Procedures of referendum, initiative and recall are unknown in Malaysia. Appointment of Pre-Legislation Committee in Parliament with NGO or public participation is entirely at the discretion of the government. Parliamentary Bills are kept secret till laid in Parliament. The UK tradition of White Papers, Pre-Legislation or Second Reading Committees in Parliament has not taken roots in Malaysia. Regrettably, local authorities are not elected but appointed by the state governments. Local government elections were a colourful feature of our political landscape but were abolished in the 70s. I. Independent Legal Profession The States of Malaya and Sabah and Sarawak have their own Bar Councils existing under separate statutes. The profession is highly regarded and has maintained its independence and integrity despite many attempts to silence it. For two decades after independence, each and every member of the Bar was foreign trained and had no direct knowledge of the Malaysian legal system at entry point. Due to official recognition of foreign degrees from the UK, Ireland, Singapore and Australia, and no requirement to do a bridging course on the Malaysian legal system before being called to the Bar, the scandalous situation was and still continues that a person can be called to the Malaysian Bar or be appointed a judge without ever having attended a course on the Malaysian Constitution. J. Legal Education and Legal Literacy Till 1972, no Malaysian university offered a course in local laws. External degrees were the only route to a legal career. However since then, the profession is being served by local law faculties as far as numbers go. Regrettably however, legal education in Malaysia is very Western-centric and remains a colonial construct. Almost all our university courses are built around the theories and assumptions of great European or American scholars. Their theories are drilled as if they are universal while ignoring or undermining other forms of knowledge. There is woeful ignorance of Eastern contributions from China, India and Persia. The books and icons remain Western. Our course in jurisprudence, our concept of law, our categories of law, our concept of human rights and human wrongs all remain Western. A further problem is that legal education is too profession-oriented and not sufficiently people-oriented. The law school does not reach out to society or to spread legal literacy. K. Constitutional Commissions The Constitution and laws have created a number of independent Commissions and Councils that are supposed to oversee particular aspects of governance. There is the Election Commission, Armed Forces Council, Judicial and Legal Services Commission, Pubic Services Commission, Police Force Commission, Education Service Commission, Anti-Corruption Commission and the Human Rights Commission. In addition we have the Auditor General and the Attorney-General. Whether these Commissions and institutions act with integrity and independence or whether they are under the control of an omnipotent executive is a matter of opinion. L. Powerful Federal Police Force The Police Force is a federal force and is charged with the responsibility of maintaining security, public order and investigating crime. However, the power to launch a prosecution lies with the Attorney-General who doubles up as the government’s chief lawyer as well as the Public Prosecutor. M. Law Reporting Law reports have existed since the 30s and their standard of reporting is quite high. Unfortunately, the responsibility of publishing is undertaken by the private sector and not by the courts themselves. As such, the cost is high and subscribing to these reports is out of the reach of most people. Most High Court cases go unreported due to shortage of space which is taken up by Court of Appeal and Federal Court decisions. Also, Malaysian law reports do not include a summary of the lawyers’ submissions and merely report the judges’ decisions. N. Legal Aid A government run Legal Aid Bureau and a Bar-run Legal Aid Centre do yeomen’s service but due to the Means Test and self-imposed limitations, the situation of legal aid in Malaysia is unsatisfactory. VI: PROCEDURES & REMEDIES A. Law-making The Constitution and laws provide for procedures for law making. At the federal level, the relevant provisions are: Articles 40, 40(1A), 44, 62, 66, 67 and 68. Bills to amend the Constitution require special procedures, special majorities and, in some cases, consent of persons or institutions outside of Parliament; Articles 2(b), 159, 161E. B. Civil and Criminal Procedure Civil and criminal trials are regulated by enacted court rules, a Criminal Procedure Code and a highly developed law of evidence. In particular, criminal justice is regulated by several statutes relating to police powers of arrest, search and seizure, admissibility of evidence, confessions, investigation, search procedures and constitutional rights of the accused. Under security laws, the police have powers to detain preventively subject to procedural compliance. There is no dearth of complainants going to the courts against the police. Judicial review of police actions is known though it is rare. A notable feature in Malaysia is that there are no jury trials. C. Prosecutorial Power The Attorney-General’s power to raise or refuse to raise prosecution, to choose the law under which to charge the accused, to transfer a case laterally or vertically has been held by the courts to be non-reviewable. If the police and the AG refuse to investigate, charge and prosecute a public official, there is nothing a citizen can do. The legal system is weak when it comes to punishing misfeasance by state officials. A civic-minded citizen will have no locus standi. He has no right to information due to the Official Secrets Act. There is as yet no right to Public Interest Litigation. Relator Actions require the AG’s consent. D. Judicial Review In the area of public law, courts have the power of judicial review on the traditional grounds of ultra vires and natural justice. Administrative law is developing well and some judges have “constitutionalised” the principles of administrative law. Thus, the right to go to the courts for judicial review is part of “personal liberty”. Natural justice is part of the constitutional promise of equality and due process. On the remedial aspects of the law, there is a multiplicity of pigeon-hole remedies among them: Certiorari, Prohibition, Mandamus, Injunction, Declaration, Quo Warranto and Action for Damages. As yet, no “public interest litigation” is available. The procedure of “Relator Action” has never been invoked. VII: LOOKING TO THE FUTURE Malaysia has a well-developed legal system. However, in some areas rethinking is necessary to achieve global standards of administrative justice, good governance, accountability and democracy. A. Supremacy of the Constitution or Supremacy of the Syariah? This is a question that is increasingly being raised. The “Islamic state” sentiment is widespread and though it has no basis in the Constitution,[119] its political appeal is immense. B. Federal-state Division of Powers Schedule 9 divides legislative power between the federal and state legislatures. Islamic personal law is in the State List. Regrettably, many State Assemblies are breaking free of constitutional limitations, trespassing on matters in the Federal List and in exercising their power, are violating the fundamental rights of Muslims and non-Muslims. The civil courts look the other way. C. Human Rights The jurisprudence of human rights is developing, but is still in its infancy. D. Jurisdictional Conflicts The last few decades have seen painful, unresolved disputes between civil and syariah courts. Article 121(1A) gives autonomy to syariah courts in matters within their jurisdiction. The problem is that even when the powerful syariah establishment exceeds its powers or violates the Constitution or infringes fundamental rights, most civil judges refuse jurisdiction to entertain the complaint even when there are issues of constitutionality and the rights of non-Muslims are being breached by the actions of syariah authorities. E. The Aborigines (Orang Asli) Despite affirmative action provision for the aboriginal people of the Malay Peninsula in Article 8(5)(c), the orang asli remain forgotten and marginalized. There is however some judicial recognition of their customary rights to land though judicial decisions have gone both ways.[120] F. Electoral Process The process of drawing up electoral lists, cleaning up these lists of unauthorised voters and delineating the constituencies is under the control of the Election Commission and Parliament. There is no openness or transparency or accountability about the process. Voters’ attempts to seek judicial review have consistently failed. The courts are not willing to enter this political thicket. G. Remedies The law on remedies is well developed but due to the technicality and cost of court proceedings, justice is not accessible to most citizens. The remedial aspects of the legal system need to be strengthened. Indigenous, non-legal, informal, inexpensive and expeditious remedies against wrongs need to be created. H. Artificial Distinctions The legal system is built on the traditional but artificial distinction between public law and private law, crimes and civil wrongs, contract and tort, municipal and international law. These distinctions do not always serve us well. For example, constitutional rights are not always available in private or contractual relationships between employer-employee, school-pupil, university-student and parent-child relationships. I. Reception of International Law Our legal system is built on the dualistic theory of international law. However, in an age of globalisation, we must dismantle the legal dykes we have built against the reception of international law. J. No Internalisation of Ideals The ideals of rule of law, separation of powers, openness and accountability in government, protection of human rights and the ideals of constitutionalism have not taken roots in our legal system. A large number of lawyers, judges, law teachers and students are legal technicians and lack a social conscience and a social perspective. Despite the above, one can harbour the hope that on the solid legal foundation that already exists we can build institutions, principles and procedures to strengthen constitutionalism and rule of law in our nascent democracy. Written by Professor Emeritus Datuk Dr Shad Saleem Faruqi, the holder of the Tunku Abdul Rahman Foundation Chair, and a lecturer in the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya. Edited by Hanan Khaleeda. Footnotes: