|

9/5/2020 0 Comments The Water Is Still Muddy: Limitations on Ancillary Trustees in Actions of Constructive TrustS.21(1) of the UK Limitation Act 1980 has revealed its unfairness as it leaves the claimants barred by limitation simply because the trust property lies in the hands of a dishonest assister. Therefore, there is a need for a statutory intervention or legislative reform to crystallise the view of the slim majority in the UK case of Williams v Central Bank of Nigeria.

I. INTRODUCTION For more than a century, the scope of limitation on actions by beneficiaries of a constructive trust against dishonest assisters or knowing recipients has continued to confound lawyers and scholars alike. Although such conundrum has been recently revisited by the UK Supreme Court in Williams v Central Bank of Nigeria (Williams),[1] the slim 3-2 decision raises more questions than answers. In Malaysia, the High Court has followed Williams[2] without delving deep into the majority and minority opinions of the four Law Lords which so sharply divided the English apex bench. The starting point of our analysis is S.21(1) of the UK Limitation Act 1980 (UK LA 1980)[3] (in pari materia with S.22(1) of the Malaysian Limitation Act 1953[4] and S.22(1) of the Singaporean Limitation Act[5]) which reads: ‘21. (1) No period of limitation prescribed by this Act shall apply to an action by a beneficiary under a trust, being an action – (a) in respect of any fraud or fraudulent breach of trust to which the trustee was a party or privy; or (b) to recover from the trustee trust property or the proceeds thereof in the possession of the trustee, or previously received by the trustee and converted to his use.’ Such section operates as an exception to the general rule prescribing a limitation period of six years on actions by a beneficiary to recover trust property or in respect of any breach of trust.[6] Simply put, such two exceptions can be characterised as the ‘fraudulent breach exception’ and ‘trust property exception’. The principal question that has triggered much jurisprudential debate is this: do the two exceptions apply to actions against a stranger to a trust who is merely liable to account as a constructive trustee on the footing of dishonest assistance or knowing receipt?

0 Comments

The COVID-19 outbreak has compelled countries worldwide to enforce lockdowns, but will such extreme measures actually save human lives or sacrifice human rights?

I. OVERVIEW The COVID-19 pandemic is truly a scourge to humanity. The death toll exceeds 100,000. Millions more are infected.[1] Fatalities continue to mount. The virus is especially vicious against the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions (mercifully leaving the young largely unharmed).[2] From Wuhan to Lombardy to New York, any corner of the world can be the next epicenter. 19/4/2020 0 Comments Shielding Individual Peace In Modern Times: Debunking The Efficacy Of The PDPA (2010) In Protecting Data And Privacy RightsThe absence of a specific law to protect privacy indicates the urgent need for Parliament to amend the PDPA in order to ensure the effectiveness of privacy protection laws in this country.

I. INTRODUCTION The right to privacy is recognised as a fundamental right under Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)[1] and Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[2] Generally, privacy refers to the state of being free from public attention, violation or misuse.[3] It represents an individual’s peace and tranquillity. However, the legal concept of and rights to privacy have been proven difficult to define despite many attempts. The Calcutt Committee[4] defines privacy as the right of an individual to be protected against intrusion into his personal life or affairs, or those of his family, by direct physical means or by the publication of information.[5] The Australian Law Reform Commission divided privacy into four interrelated concepts,[6] known as information privacy,[7] bodily privacy,[8] privacy of communications[9] and territorial privacy.[10] In retrospect, the earliest and most widely used description to define the right to privacy was ‘the right to be let alone’, coined by Justice Cooley in 1888.[11] Although this widely accepted definition remains elusive, privacy is undeniably multi-dimensional. It comprises of the right to be left alone, the right to exercise control over one’s personal information, and the right to protect one’s dignity and autonomy.[12] In the recent decision of Macvilla Sdn Bhd v Mervyn Peter Guan Yin Hui and Another, the Court of Appeal revisited the principles on forfeiture of deposits and the treatment of liquidated damages clauses in contracts that had been adopted and discussed by the Federal Court in Cubic Electronics v Mars Telecommunications in 2018.

I. INTRODUCTION The Federal Court decision in Cubic Electronics v Mars Telecommunications[1] was generally welcomed by members of the legal fraternity as well as the construction and related sectors in Malaysia as being a commercially sensible and much needed restatement of the law on damages clauses. Prior to the said Federal Court decision, the use of damages clauses in most contracts was severely limited by Malaysian law pursuant to Section 75 of the Contracts Act 1950 (‘S.75 CA’). The Federal Court in Cubic Electronics held that S.75 CA allows the use of damages clauses unless they are proven to be penalty clauses and, inter alia, that S.75 CA would apply to the forfeiture of deposits. This landmark decision generated a great deal of interest from academicians as well as practitioners and has been cited with approval in a number of High Court decisions as well as a Court of Appeal decision.[2] However, the Court of Appeal subsequently handed down a rather unexpected decision in the case of Macvilla Sdn Bhd v Mervyn Peter Guan Yin Hui and Another (‘Macvilla’).[3] The Macvilla judgement appears to be critical of the approach taken by the Federal Court in Cubic Electronics.[4] While most of its statements on the law are obiter, the decision may well generate some confusion with regard to the clear restatement of the law on S.75 CA by the apex court. Sexual harassment is an unwelcomed behaviour that is offensive, humiliating or intimidating. As the government scrambles to find a solution, what does the future hold for a sexual harassment bill?

I. INTRODUCTION The global #MeToo movement as well as the Harvey Weinstein scandal have sparked controversy and a growing awareness on the plight of sexual harassment victims — drawing the local community’s attention to cases closer to home. In 2018, a specialist doctor from a public hospital in the Klang Valley was dismissed for various counts of sexual harassment counduct towards his female housemen. This case was brought to the attention of the former Health Minister Dzulkefly Ahmad, all the way to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, who had consented to this doctor’s dismissal.[1] Nevertheless, the doctor was not criminally prosecuted and the case was not pursued further. The Federal Constitution is the supreme law of the land in Malaysia. Yet, like all laws, it must be capable of change. However, how much change can the constitution be subject to by a majority political faction before it becomes unrecognisable? I. INTRODUCTION The basic structure doctrine is no stranger to disciples of the law. Frequently tied in with the issue of constitutional amendments, the basic structure doctrine, as its name suggests, posits that there are several features within the Constitution that form the basic fabric of our nationhood, and cannot simply be taken away by virtue of a constitutional amendment or a legislation propounded by Parliament. The brainchild of judicial activism, this seminal doctrine which arose from the Indian constitutional courts has found its place within Malaysian jurisprudence. For many years, it was a doctrine which was felt but not seen, as many Malaysian judges had been in the past sceptical of its compatibility with local circumstances. However, after the luminous decisions of the Federal Court in Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat[3] and Indira Gandhi v Pengarah Jabatan Agama Islam Perak,[4] there is no longer any reason to question its importance. 28/2/2020 0 Comments Picking Up the Pieces: The Dissolution and Formation of Coalition Government in Wake of the ‘Sheraton Move’One fateful Sunday, the coup attempt labelled as the ‘Sheraton move’ disrupted the usual two-coalition political configuration in the country, sending Malaysia into a state of political turmoil. I. INTRODUCTION

The events of the past four days raise several questions regarding the constitutional ambiguities of the legal framework governing the breakdown of a governing coalition and subsequent attempts to form a new government. In several instances, the events that have transpired over the past four days, have intimated some fragmentary answers or, at the very least, demonstrated the attitude of institutional actors such as the Prime Minister, Attorney General, and Palace officials during such a political crisis. Although some of these questions are moot given the emergence of a political consensus, they nonetheless shed light onto the difficulties at the interface between codified constitutional rules — most of which were promulgated in 1957 — and the dynamism of contemporary political events. Erinford injunction is one of the types of injunctions provided in court. Although it has not been formally introduced in Malaysian statutes, this does not restrict its usage and development in the courts of Malaysia. I. INTRODUCTION

An injunction is a relief in the form of a court order, which forbids or compels a specified party from doing a certain act. Based on equitable principles, it is normally granted when damages is not an adequate remedy. There are different types of injunctions available, namely temporary (interlocutory or interim) injunctions, perpetual (final) injunctions, injunctions to perform a negative agreement, and special injunctions. The subject matter of this article, the Erinford injunction, is one of the few special injunctions developed through case law. 12/11/2019 3 Comments An Analysis on The Development of The Derbyshire Principle in Malaysia: Can You Speak Now?The Derbyshire principle has always protected citizens from actions of defamation in the wake of governmental dissent or issues raised against the government. However, this protection has since been removed in Malaysia I. INTRODUCTION Gone are the days for detractors to make statements against the Malaysian Government without fear. In its recent ruling of Government of Sarawak v Chong Chieng Jen,[1] the Federal Court has made a definite yet controversial decision to lift the ban for the government or public authorities to sue its citizens for defamation. The government can now launch a legal suit on defamation against any normal citizens. This overruled principle, commonly known as the Derbyshire principle, originates from the House of Lord’s decision of Derbyshire County Council v Times Newspaper in 1993.[2] It has since served as a principle to deny governmental body’s right to sue for defamation in common law countries. The problem of plastic pollution is more focused on by the public than microplastic pollution. Many think that both are one and the same, but inherently they are different. More efforts should be made to recognise this problem and to engage in it directly.I. INTRODUCTION

Microplastics are scientifically defined as plastic fragments that are less than 5mm[1] or, in simpler terms, they are equivalent to tiny pieces of plastic that pollute the environment. Most do not know that microplastics can be further classified into two, which are primary and secondary microplastics. 16/9/2019 2 Comments Dilution of Banker's Duty of Secrecy in Malaysia under the Financial Services Act 2013: An Adventure Too Far?A banker’s duty of secrecy has been statutorily codified even in predecessing statutes prior to the coming into force of the Financial Services Act 2013 ('FSA'). The FSA has allowed for a wide scope of permitted disclosures of customer information, and this superficially constitutes a major inroad into the duty of secrecy owed by bankers to their customers.

I. INTRODUCTION Swift fly the years, it is 2019 and the Financial Services Act 2013 (‘FSA’)[1] has just celebrated its sixth birthday. This piece of legislation was intended to boost Malaysia’s financial sector, which encompasses the banking system, the financial markets and other financial intermediaries.[2] Over the past six years, we have seen the gradually robust implementation of the FSA. However, lurking in the shadow is the issue of a banker’s duty of secrecy towards customers, which received statutory codification way back in the FSA’s predecessor statutes. The coming into force of the FSA allowed for a wide scope of permitted disclosures of customer information, and this superficially constitutes a major inroad into the duty of secrecy owed by bankers to their customers. Yet, the government and other stakeholders of the financial sector are always quick to assure the masses that such dilution is justified and necessary. Therefore, this article seeks to examine the current legal position on the banker’s duty of secrecy under the FSA and scrutinise the prescribed permitted disclosures. The author will then analyse whether the considerable amount of statutory exceptions dilute the duty of secrecy and whether there are justifiable grounds for such dilution. Before concluding the article, the author will also briefly look into the Personal Data Protection Act 2010 to see whether it addresses or exacerbates the dilution. It must be noted that the focus of this article is only on the FSA and does not include the relevant provisions in the Islamic Financial Services Act 2013.[3] Digital States, where nationalities are forged by ideology rather than geography. I. INTRODUCTION

The modern notion of statehood as we know it is rooted in the Treaty of Westphalia that concluded the European religious wars in 1648. Statehood is the core of the current international legal system, because the entire international legal system was originally conceived as a system of rules governing the relations of states. However, the world has changed tremendously since 1648. We have gone through three industrial revolutions and the incoming fourth industrial revolution is already blurring the lines between the physical and digital worlds. Technological revolution today gives rise to a new concept of a “Digital State”, which is an idea of building states online which are not geographically demarcated. The idea is not entirely novel, but it has resurged recently given the advancement in our technological capabilities as well as the change in the political and environmental climate that the world is currently facing.[1] We are witnessing increasing movement of people across countries due to globalisation and humanitarian crises. It is estimated that there could be as many as 200 million climate-change refugees by 2050.[2] At the same time, a substantial number of people are connected to each other via the internet. Hence, the question arises as to whether it is possible to build a state that is based on proximity of ideas on cyberspace instead of a traditional state that is build on proximity of distance? 4/8/2019 1 Comment An Assessment of the Peaceful Assembly (Amendment) Bill 2019: Bouquets and BrickbatsMalaysians' right to freedom of assembly, although cemented in the Federal Constitution, is a qualified right which may be restricted by the Parliament. The Peaceful Assembly (Amendment) Bill 2019 represented an opportunity for the rakyat to be better protected and secured in exercising their right to assemble. I. INTRODUCTION

Malaysians’ right to freedom of assembly is cemented in Article 10(1)(b) of the Federal Constitution. Nevertheless, it is a qualified right whereby the supreme law of the land permits the Parliament to enact laws imposing restrictions on two permissible grounds—national security and public order.[1] In 2012, the Peaceful Assembly Act 2012[2] (“PAA 2012”) was passed, seeking to assure an individual’s right to assemble peacefully as part of the right of expression enshrined in the Federal Constitution. However, this piece of legislation was criticised as a “flawed law that operates on a skewed premise”.[3] Besides, the chorus of calls for major amendments or a total overhaul of the Act have been heard for some time, and some members of the public even advocated for the Act to be repealed altogether. On 4 July 2019, the Peaceful Assembly (Amendment) Bill2019[4] (“Amendment Bill 2019”), tabled by Home Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, was passed by the Dewan Rakyat. Subsequently, on 24 July 2019, the Amendment Bill 2019 was passed by the Dewan Negara. The amendment represented an opportunity for the rakyat to be better protected and secured in exercising their right to peaceful assembly. Therefore, this article seeks to determine whether such chance is utilised or lost by evaluating the salient features of the Amendment Bill 2019. 14/7/2019 2 Comments Double Trouble No More: The Striking Down of Double Presumptions for Drug Trafficking by The Federal CourtThe war against drugs is far from over but the Federal Court has nevertheless stepped in to put an end to the reign of double presumptions in drug trafficking cases.

I. INTRODUCTION Malaysia’s commitment to fighting drugs has always been associated with its draconian drug laws, known to be one of the strictest in the world. However, a perusal of those laws would lead to a finding that one of the many fundamental ideals inherent in the rule of law, viz., the presumption of innocence, seems to be undermined. The Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 (‘DDA’),[1] the primary law governing drug offences in Malaysia, via Section 37A (‘s.37A’) allows the use of double presumptions, viz., the presumptions under Section 37(d) (‘s.37(d)’) and Section 37(da) (‘s.37(da)’) of the DDA could be used together to prove “possession and knowledge” and thereafter to prove “drug trafficking”. Hence, the DDA has transferred the onus of proof so that, once the facts necessary to constitute the crime is proven, the accused will be held to be guilty unless he can disprove the presumptions. This serves as a powerful tool for the prosecution. 1/5/2019 1 Comment Combating Asymmetric Warfare, Artificial Intelligence and Terrorism: Can International Humanitarian Law Withstand the Test of Time?International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is a law that is meant to protect innocents from the sufferings of war. Challenges now stand between the original objective of the IHL and the actual reality of warfare. I. INTRODUCTION

War invariably causes indescribable pain and suffering. Left unregulated, it devastates millions of lives — civilians and combatants alike. This is where International Humanitarian Law (‘IHL’) comes into the picture to safeguard humanity. The purpose of its existence is to alleviate the sufferings of civilians and persons hors de combat[1] during war. It is a given that minimum standards of humanity within the ambit of IHL must be respected and met in any situation of armed conflict. What’s more, a balance must be struck between military necessity[2] and basic sense of humanity. IHL allows parties to the armed conflict to impose drastic measures during war to overcome an adversary. For example, it may be militarily necessary to cause death of the belligerents. However, this is only permitted if humanity is considered. To this end, restraints and limitations on means and methods of warfare[3] have been put in place for the waging of war; also, humane treatment must be given to prisoners of war.[4] Today, 196 nations have ratified the four Geneva Conventions.[5] It is clear that IHL has evolved into one of the most substantially codified branches of international law which is globally relevant. Therefore, its humanitarian principles should be consistently upheld by all state parties and their subjects. 25/4/2019 2 Comments An Exclusion Clause Wrongly Ousted: A Well-Drafted Exclusion Clause Misinterpreted on Many LevelsWhat does not seem to have been decided in all the established common law jurisdictions is that an exclusion clause would be considered as an ouster of the court’s jurisdiction as decided by the Federal Court in CIMB Bank Berhad v Anthony Lawrence Bourke & Anor.

I. INTRODUCTION The recent Federal Court decision in CIMB Bank Berhad v Anthony Lawrence Bourke & Anor[1] was not so unexpected given the arguments adopted by the counsels and the unfortunate position of the Plaintiffs who were individual customers/borrowers of a leading bank. What is regrettable is that, in its attempt to do justice to the party with the weaker bargaining power, the Federal Court may have unnecessarily chosen to disregard well-established legal principles of contract law and rendered the work of drafting contracts more difficult. 2/3/2019 0 Comments Understanding Coram Failure: Tidal Waves from the Federal Court Decision of Bellajade v CME Group & Tan Sri Lim Cheng PowWhether the Federal Court's decision in setting aside its previous decision on the ground of 'coram failure' was rightly made? I. A BRIEF HISTORY OF BELLAJADE V CME GROUP & TAN SRI LIM CHENG POW

In the recent judgment on Bellajade v CME Group & Tan Sri Lim Cheng Pow, the Federal Court set aside a judgment it delivered last year on the ground of coram failure. The Federal Court had heard the case at an earlier date and reserved judgment until 25 September 2018. Then, on the 31st of July, Tan Sri Zulkefli Ahmad Makinudin resigned by virtue of Article 125(2) of the Federal Constitution.[1] On the 25th, Tan Sri Azahar Mohamed pronounced in court the written judgment authored by Tan Sri Zulkefli on his behalf. The judgment, being the sole composition and reasoning of Tan Sri Zulkefli, was concurred and adopted by three other judges, who then comprised the majority. The judgment was contested by the appellants under Rule 137 of the Rules of Federal Court (RFC) which states the Federal Court’s inherent power to hear applications to prevent injustice.[2] The judgment was argued to be inoperative because it was pronounced in an open court only after Tan Sri Zulkefli’s resignation, when he was no longer an active member of the court. This situation may be termed as ‘coram failure’. 10/2/2019 2 Comments A Stunning Restatement of the Law on Liquidated Damages Clauses by the Federal CourtRichard Malanjum, Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak (as he then was), answers the question on the effectiveness of having liquidated damages clauses in contracts and whether such clauses are enforceable in Malaysia in the recent Federal Court decision of Cubic Electronics Sdn Bhd (In liquidation) v Mars Telecommunications Sdn Bhd.

I. INTRODUCTION The Federal Court decision in the case of Selva Kumar Murugiah v Thiagarajah Retnasamy[1] (“Selva Kumar”) on the scope of Section 75 of the Contracts Act 1950 (“S.75 CA”) has left many questioning the effectiveness of having liquidated damages clauses in contracts and whether such clauses are in fact enforceable in Malaysia. Many judges, lawyers and industry leaders share the view that liquidated damages clauses are effective and important means by which parties to a contract are able to negotiate and agree upon entering into the contract as to the compensation payable for non-performance of contractual obligations.[2] Such clauses aim to reduce the need for costly and time-consuming court proceedings in the event of a breach and provide commercial certainty for contracting parties with regard to the risks they undertake in the contract. Judicial support for these liquidated damages clauses are found in most common law jurisdictions[3] and their importance to the construction industry in particular is well recognised.[4] 30/1/2019 1 Comment Suicide: A Tragedy or a Crime?Suicide and attempted suicide are criminalised in Malaysia, but is that the right reaction to such an emotional upheaval? I. INTRODUCTION

‘No matter how much pressure you are facing, suicide is not a solution. Now that you’re out of the hospital, you must be charged in court. You must know that attempting suicide is a crime.’ These were the words uttered to an unemployed 24-year-old, Yew Kah Sin, who had the burden of her mother’s lung cancer treatment riding on her back as the courts sentenced her to a fine of RM2,000 or three months’ imprisonment after she tried killing herself early of 2017.[1] Sad as it is to admit, ‘suicide’ has become a common term to read in the papers today as many attempt to end a beginning they have yet to see out of blind desperation. The current legislation, however, seems to deal with these recurring cases by punishing those who attempt to commit suicide with fines or terms of imprisonment. On this matter, Hannah Yeoh, the Minister of Deputy Women, Community and Family Development recently claimed that the criminalisation of suicide is archaic and should be reviewed.[2] This article aims to explain the legal position of Malaysia on suicide and the differing views on whether such a position should remain in today’s society. 20/12/2018 1 Comment Opt-out Organ Donation Law: Silver Bullet or Fool’s Gold for Organ Shortage in Malaysia?Is the opt-out system the answer to filling the gaps between demand and supply of human organs? I. INTRODUCTION

The gap between the demand and the supply of human organs for transplantation in Malaysia is on the rise, despite the efforts of the government to promote donor registration. The supply of organs in Malaysia suffers from a persistent chronic dearth, which results in many people who need organs suffering and dying while on waiting lists.[1] Several countries have opted for a change in legislation and introduced an opt-out system, whereby cadaveric organ procurement is based on the principle of presumed consent to increase the number of donations. Cadaveric organ donation is the donation of organs after the death of an individual. Such individual is classified as a potential donor in the absence of explicit opposition to donation during the individual’s lifetime. It is interesting to note that the English government recently announced its plans to change the law on consent for organ donation.[2] The new opt-out system, known as Max’s law, seeks to be in place by 2020 in England, if Parliament grants approval. 15/11/2018 1 Comment THE LAW MUST NOT STAND STILLLaw is a living growth and not a changeless code. All societies are dynamic and no law can make time stand still. Law Reform Commissions or Institutes can provide principled and imaginative new law. They can be catalysts of change, responsive to the world around them and to the public they serve. It is time we recognise their role as moderators, modulators and mediators of change. *This is an unedited original manuscript. INTRODUCTION Law is an indispensable attribute of every civilised society. Formulating, interpreting and enforcing a simple, fair, modern and efficient system of law is a challenge as tall as the trees, as deep as the seas. Why this is such a formidable challenge is not so difficult to understand.

Antiquity: There is a proliferation of laws and this is matched only by their obsolescence. Life is larger than the law and no formal system of norms can cope with the complexities, probabilities and pitfalls that accompany life’s endeavours. All societies are dynamic and no law can make time stand still. Law is a living growth and not a changeless code. The felt necessities of the times demand a constant reform of legal instruments to cope with social and economic realities. Laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of society, technical innovations and increasing globalisation. 23/10/2018 0 Comments The Inception of Pre-trial Processes: Closing Legal Loopholes or Opening Pandora’s Box?The 2010 Amendments, an attempt to expedite criminal trials. I. INTRODUCTION

Pre-trial processes were introduced into the Criminal Procedure Code (Amendment) Act 2010[1] and have since been encapsulated in Chapter XVIIIA of the Criminal Procedures Code[2] (“2010 Amendments”). The 2010 Amendments embody Parliament’s spirit of resolving the backlog of cases and promoting speedy trials in line with the Malaysian Government Transformation Programme.[3] Further, the 2010 Amendments were also spurred by the then Chief Justice Tun Zaki Azmi’s initiative to deliver justice more expeditiously.[4] This article will elucidate the three main components of pre-trial processes – pre-trial conference, case management and plea bargaining, and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the pre-2010 and post-2010 Amendments through the lens of the Court, defence, prosecution, and victim (“Parties Concerned”). Attempts will be made to ascertain whether these amendments are for the better or the worse. If these amendments do indeed bring disadvantages to the Parties Concerned, the author will determine which pre-trial regime, pre-2010 or post-2010, is the lesser of two evils. Child marriage is presently legal for both Muslims and non-Muslims respectively. Owing to the recent headlines of reported cases of child marriage, this issue has re-emerged as a hot-button issue, with numerous calls to end the practice of child marriage.

I. INTRODUCTION The issue of child marriage sparked outrage in Malaysia owing to the controversial marriage of an 11-year-old girl to a 41-year-old man.[1] Malaysians have expressed grave concerns about the incident, resulting in clarion calls from many quarters to raise the floor age of marriage to 18. This call is especially pertinent in light of Pakatan Harapan’s pledge in its manifesto for the 14th General Election, which was to “ensure the legal system protects women’s rights and dignity”, including “introducing a law that sets 18 as the minimum age of marriage”.[2] However, the nation is currently witnessing the controversial handling of child marriage issue by the Women, Family and Community Development Ministry, headed by Datuk Seri Dr. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail. The minister has received brickbats with reasonable justifications as it has been two months since the incident occurred, but there is yet to be any significant resolution proposed.[3] The answer to the people’s cries was repetitive — that the federal government does not have jurisdiction to intervene in child bride cases. Yet another case of child marriage was reported on the 18th of September in Kelantan where a 15-year-old girl tied the knot with a 44-year-old man, who is a father of two.[4] The author is of the opinion that the longer the ministry delays in reacting towards this controversial issue, the higher the number of young girls who will fall victim to child marriage and have their welfare and interest jeopardised. The High Court here has granted an interim gag order against the media from discussing the "merits" of Dato' Sri Najib Tun Razak's case Image credit: https://goo.gl/WAECbg I. INTRODUCTION

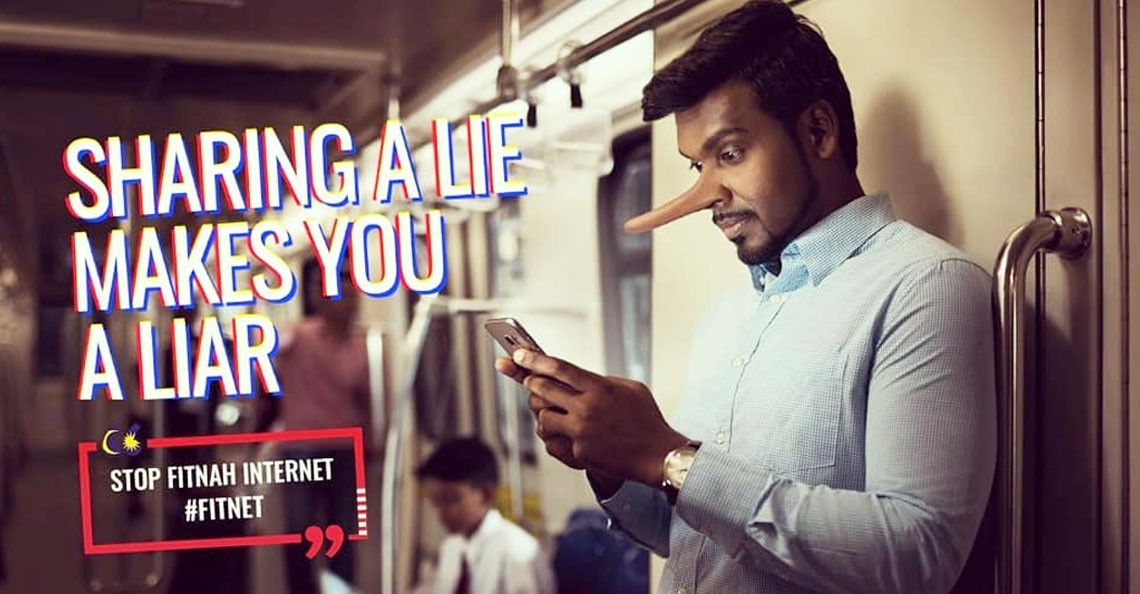

Recently, the arrest of former premier Dato’ Sri Haji Mohammad Najib bin Tun Haji Abdul Razak (Dato’ Sri Najib Tun Razak) garnered massive attention from the rakyat and the world. In response to such scintillating news, the Malaysian media outlets have given vast coverage on this issue from the moment of arrest up until the hearing before the Kuala Lumpur High Court. Tenaciously, these media outlets prescribed the background information and details of this arrest, which happened due to graft allegations in the management of the 1Malaysia Development Berhad subsidiary known as SRC International Berhad by Dato’ Sri Najib Tun Razak and his counterparts.[1] Public were generally cautioned in spreading news through online platforms. Anti-Fake news posters could be seen at public places such as Light Rapid Transit (LRT) and bus stations. Image credit: https://cilisos.my/wait-why-do-we-need-fake-news-laws-when-we-have-defamation-laws/ I. INTRODUCTION

As technology advances with time, the dissemination of fake news is becoming a global concern which affects the safety, economy and well-being of most countries. For instance, there is a widespread concern expressed in the United States (“US”) that the 2016 US Presidential Election (“2016 Election”) saw online falsehoods spread by private actors and Russia. Back in Malaysia, fake news has led to a shoe company, Bata Primavera Sdn Bhd, losing more than RM500, 000 in just a month after an allegation that went viral about the company selling shoes with the Arabic word “Allah”.[1] Fake news also sparked unnecessary public confusion when a fire broke out at the Employees Provident Fund (“EPF”)’s building and people began panicking that their EPF savings were affected by the fire.[2] Needless to say, the recent 14th General Election also observes an abundance of unverified election news spreading on media outlets. |

CategoriesAll Comments Criminal Law Environmental Law Law And Society UMLR |

|

|

PhoneTel : +603-7967 6511/6512

Fax : +603-7957 3239 |