|

26/5/2022 30 Comments Right of Refugees in MalaysiaWritten by Wallace Kew JiaRong and Chia Jia Xuan, third-year Bachelor of Laws students from Universiti Malaya. Edited by Cheng Xin Miao. Reviewed by Chelsea Ho Su Ven. This article aims to shed light on the plight of refugees mounting from their dearth of legal status in Malaysia. Refugees in the country often find themselves in a vulnerable state. On one hand, they face potential salary reductions and other forms of exploitation from their employers. On the other hand, refugee children are deprived of their rights to formal education — the gateway to a brighter future, a chance to meliorate their life quality. Yet, when faced with iniquity, they are unable to defend themselves by legal means as they risk detention and deportation for their illegal immigrant status. I. DEFINITION OF REFUGEES IN MALAYSIA

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (‘UNHCR’), is a person who is situated outside their country of nationality or habitual residence and is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin — owing to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion.[1]

30 Comments

Written by Siti Sarah and Shafiq Zafran from the Asian Law Students Association of the University of Malaya. Edited by Chrystal Foo. Reviewed by Luc Choong and Celin Khoo Roong Teng. It is irrefutable that the right to vote is intrinsic to a democratic state. In Malaysia, this right is safeguarded by the Federal Constitution. However, the mere right to vote is not enough to ensure a free and fair election. This article aims to spotlight occurrences that have tainted this inherent right and efforts that have been taken to circumvent such instances.

I. INTRODUCTION A. Elections and Electoral Fraud The power to govern and change the course of destiny gets rewritten after every systemic change of ruling. In the Malaysian political context, the primary form for a change of ruling is conventionally done through an election. Generally, a general election (‘GE’) is hosted around every five years to ensure that democracy maintains as a staple in the Malaysian community. The Malaysian Government comprises three branches: the Executive, the Judiciary and the Legislature. This article will emphasise the Executive that is spearheaded by the Prime Minister as the primus inter pares. The appointment of the Prime Minister falls under the Yang di-Pertuan Agong’s discretionary powers by virtue of Article 40(2)(a) of the Federal Constitution.[1] Malaysia practices parliamentary democracy; thus, the party or coalition with the absolute majority in Parliament will be declared as the government of the day, with its leader conventionally assuming the post of Prime Minister. Written by Quek Yew Aun and Selvapandiyan a/l Krishnan, second-year Bachelor of Jurisprudence students, University of Malaya; and Vishal a/l Gopinathan, Advocate and Solicitor of the High Court of Malaya. Edited by Chrystal Foo. Reviewed by Luc Choong and Celin Khoo Roong Teng. For students in Malaysia, textbooks are often a scarce and expensive resource. This situation has led to the widespread practice of photocopying textbooks and use of electronic copies as reference. However, the legality of such practices in Malaysia is unclear. Textbooks come under the definition of ‘literary works’ and hence their copyright is protected by the Copyright Act 1987. The legality of photocopying and common practices of textbook dealings was examined based on the Copyright Act 1987, decided cases in Malaysia and the Commonwealth.

I. INTRODUCTION The start of every semester as a student is almost always accompanied by a brief period of confusion. Among some of the most common questions asked would be the subjects to register for, names of lecturers and number of assignments. However, in the momentary dissonance, a routine always exists: the search for textbooks. Written by Harsimran Kaur and Neha Navalashini Sominadu from ECOLAWGY UM, University of Malaya. Edited by Siti Sarah Ikmal Hisham. Reviewed by Luc Choong and Celin Khoo Roong Teng. Being home to an astonishing ecological legacy, wildlife-related crimes such as poaching, trafficking, smuggling and illegal hunting are no longer alien to us. Legislation has been enacted to circumvent these issues, but their ineffectiveness in deterring crime called for their inevitable demise, thus marking the birth of the Wildlife Conservation Act 2010 (WCA). Admittedly, the WCA has been celebrated to be the most progressive wildlife conservation act in Malaysia. I. INTRODUCTION

Malaysia is one of the seventeen megadiverse countries globally, home to a wide array of ecosystems, both marine and terrestrial.[1] The core of its terrestrial biodiversity lies in tropical rainforests — a remarkable ecological legacy that has developed over 130 million years resulting in various flora and fauna. However, such rich biodiversity is no stranger to perilous situations. In Malaysia, countless species are threatened by poaching, trafficking, smuggling across national borders, hunting without a license for international trade and encroachment into protected areas.[2] Illegally harvested wildlife from our rainforests may eventually make their way into pet trades or be consumed as exotic meat and traditional medicine.[3] Legislation enacted for the protection of terrestrial wildlife in Malaysia varies according to jurisdiction. In Malaysia, the Federal Constitution provides for the protection of wild animals and wild birds under the Concurrent List (List III of the Ninth Schedule).[4] This means that both the federal and state government may enact laws to protect wildlife. The first attempt to harmonise wildlife laws on the federal level came in the form of the Wild Animals and Birds Protection Ordinance 1955.[5] However, the Ordinance was afterwards updated and replaced by the Protection of Wild Life Act 1972 (PWLA) which applies to Peninsular Malaysia and the Federal Territory of Labuan.[6] Wildlife in Sarawak and Sabah are respectively governed by the Wild Life Protection Ordinance 1988[7] and the Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997.[8] 10/3/2021 0 Comments Towards Liberating the Native Territorial Domain in Sarawak by Adopting the Torrens SystemWritten by Fabian Meringgai ak Sebastian, a third-year law student of the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya. Edited by Chelsea Ho Su Ven. Reviewed by Luc Choong and Celin Khoo Roong Teng. Indisputably, Sarawak is rich in its nonpareil cultural diversity, which brings about the peculiar legal status of native customary land in the state. The natives’ proprietary rights over traditional land are deeply rooted in the various social practices and customs of the native ethnicities therein. Throughout this article, the author unveils his outlook on the Sarawak state government’s initiative towards protecting native customary land in peril. I. UNDERSTANDING THE TORRENS SYSTEM

The Torrens system is a land registration system introduced in South Australia by Sir Robert Richard Torrens in 1858.[1] The introduction of which in Malaysia and its subsequent emergence has presumably played a role in resolving the intricacies of land ownership faced in the country, especially in Sarawak. Under this system, the registration of land functions as conclusive evidence signifying the ownership and interests attached thereto. The objective of the Torrens system can be seen in a statement made by Lord Watson in Gibbs v Messer,[2] that is ‘to save persons dealing with registered proprietors from the trouble and expense of going behind the register, in order to investigate the history of their author’s title, and to satisfy themselves of its validity’. There are two fundamental principles of the Torrens system, namely the mirror principle and the curtain principle. The mirror principle portrays a concept in which the land title mirrors all relevant and material details that a prospective purchaser, lessee and chargee ought to know. This means that a person can obtain all such material information of the land, based on what is endorsed on the register document of title and the issue document of title — thereupon improving the efficiency of land transactions. On the other hand, the curtain principle is a concept that dispenses with the need to look beyond the register — a metaphoric curtain — as the land title itself provides all relevant information reflecting the validity of the same. Ostensibly, this ‘curtain’ is where the principle took its name from. Written by Leezzie John, a second-year law student of the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya. Edited by Luc Choong. ‘Bibik’, ‘Kakak’, ‘Nenek’ — domestic workers throughout Malaysia go by many names. Akin to millions of domestic workers across the globe, they work laboriously from dusk to dawn to keep many family units afloat. Despite their important roles, domestic workers are often left with the short end of the stick, suffering behind closed doors.

I. INTRODUCTION Domestic workers are the unsung heroes of countless families. They work around the clock and contribute to private households by cooking, cleaning, caring for children, tending the elderly and so much more.[1] As it currently stands, it is estimated that at least 52.6 million adults work as domestic workers globally in 2010, along with 7.4 million children below the age of 15.[2] However, due to the often hidden and unregistered nature of this work, the total number of domestic workers could be as high as 100 million.[3] To put things into perspective, if all domestic workers worked for a single country, the country would be the tenth largest employer worldwide.[4] Written by Bo Chi Chian, a first-year law student of the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya. Edited by Toh Zhee Qi. Contracts are often deemed as sophisticated documents involving complicated commercial transactions. The public holds a preconceived notion that the formation of contracts cannot be easily explained as several legal principles are involved. In fact, a contract is a product of the ‘meeting of the minds’ between the parties and have long been part and parcel of our daily lives.

I. INTRODUCTION Thousand-dollar bills, hundred acres of land, and spectacular buildings with splendid designs — for most people, these items pop into mind when they think of the word ‘contracts’. However, the use of contracts extends far beyond these luxurious dealings. Contracts are everywhere. Here are three examples to illustrate contracts in everyday life. You saunter by a street and an advertisement catches your eye — it pledges to pay one thousand dollars to customers who fall sick after consuming their medical products. Convinced by the guarantee, you purchase the products and follow the prescribed instructions.[1] Next, you grab a parking ticket from the automatic ticket machine before leaving your vehicle at the car park.[2] Lastly, you look into the eyes of your most beloved who gets down on one knee, and without hesitation, you say, ‘Yes, I do.’ All these acts result in ‘you’ entering into a contract with another party. The pertinent questions which arise are: What is a contract? Can ‘contracts’ be explained in a simple, direct, and one-sentence way? The doctrine of consensus ad idem may be the answer to these questions. This article seeks to illustrate ‘meeting of the minds’ in a contract through various examples. Written by Nur Zarisa binti Mohd Zait, a first-year law student of the Faculty of Law, University of Malaya. Edited by Tan Jia Shen and Celin Khoo Roong Teng. Reviewed by Zafirah Jaya. Money laundering can be perceived from two opposing perspectives. It serves one’s materialistic lust, yet it also exists as one of the contributors to a destabilised economy. Malaysia has several established policies and legislation to curb the menace.

I. INTRODUCTION On 28th July 2020, Malaysia marked history when Dato’ Sri Najib Tun Razak became the first former Prime Minister to be convicted of abuse of power, breach of trust, and money laundering. He was guilty of all seven charges relating to the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal, in which he siphoned billions of dollars of funds into his personal account.[1] Malaysians rejoiced when the verdict delivered by High Court judge Justice Mohd Nazlan Mohd Ghazali brought victory in combating money laundering offences among corrupt politicians and government officials. As the joy slowly wore off, alongside the celebration sparked curiosity: what exactly is ‘money laundering’ and how does it work? Money laundering has been in existence for centuries. Mass media and entertainment industries have portrayed dirty money on the big screen to educate viewers on the menace of money laundering and how criminals escape their liability. While some consider huge-scaled money laundering as filthy acts that contribute to financial crises, others yearn to enjoy luxurious lifestyles living off siphoned wealth — sailing on 300-foot million-dollar yachts, spending billions on Picassos and Van Gogh, or wagering in casinos. Thus, we wonder: is money laundering an art for which money is obtained through manipulation in serving our endless materialistic lust? Or is it a menace — a hidden threat that saps the economy and destabilises the government. This article caters to the average layperson by providing an insight into money laundering and highlighting policies as well as legislation in place to combat it. 30/4/2020 2 Comments Cancelled, Rescheduled & Ceased Flight: Compensatory Rights Under The Malaysian Aviation Commission Act 2015The Covid-19 pandemic has severely affected the aviation industry, with numerous airlines forced to cancel flights or cease operations all together. Fortunately, the Malaysian Aviation Commission Act 2015 provides both rights and remedies to protect consumers in these turbulent times.

I. INTRODUCTION In light of the recent health pandemic, Covid-19, multiple industries across the globe have been adversely affected. This is especially true to the civil aviation industry as the outbreak caused many unforeseen disruptions.[1] Flights being ceased, rescheduled, and cancelled are a common sight at airports worldwide, causing public outcry over the inability to get a full refund. With the passing of the Malaysian Aviation Commission Act 2015 (MAVCOM Act),[2] what are the statutory rights that have been made available to protect consumers’ rights in Malaysia under such circumstances? This article aims to shed light on the rights and remedy of consumers arising out of cancelled, ceased or rescheduled flights. 2/2/2020 0 Comments The Auspicious Quest to Embrace Good Samaritans in Malaysia: The Food Donors Protection Bill 2019Food donation is a highly encouraged act of charity but many often do not donate in fear of accidentally incurring civil or criminal liability should a person be negatively affected by said donation. The Food Donors Protection Bill 2019 is expected to help alleviate these worries. I. INTRODUCTION

The trend in our homeland is apparent — more entities are jumping on the bandwagon in donating their excess perishable food to those in need via charities and non-profit organisations.[1] However, the common concern among these entities is their liability should anything happen to the recipient due to consumption of donated food. To assuage such concerns, there are calls to enact a food donors protection law in Malaysia to encourage more entities to give away their excess food. Given the moniker ‘Good Samaritan law’, such legislations would normally protect food donors from civil and criminal liability arising out of food donations, thus giving the donors a sense of assurance.[2] Incest, despite being generally accepted as a deviation from the norm of conventional sexual behaviour, continues to fill the news with reports of such biological wrong. As a country proud of our strong ethics, this evil crime must be combatted in Malaysia to help present and future victims. I. INTRODUCTION

On 28th July 2017, a shocking report by the New Straits Times revealed that a girl was raped by five of her own relatives at various locations in Limbang, Sarawak. The accused were the victim’s own father, grandfather and three other relatives aged between 16 and 72 years old. Consequently, they were charged under S.376B for statutory rape which provides for a maximum of 30 years’ imprisonment and whipping upon conviction. [1] Unfortunately, such abhorrent news is merely the tip of the iceberg. According to a report by the Women’s Aid Organisation (WAO), a total of 296 cases of incestual relationships were reported in 2017.[2] Amongst those, 115 of them involved children between the age of 13 to 15, while 8 other cases concerned the youngest age group of 6 years old and below.[3] Children have been the victims of a majority of these reported cases, with 376 culprits being their trusted family members. As grave as the statistics may be, it nevertheless fails to depict the severity of this issue as consensual incest relationships are largely unreported, even when uncovered by another family member, in fear of the humiliation it will bring to the family name.[4] This article intends to shed some light on Malaysia’s thorn in the flesh — incest, by analysing the relevant statutory provisions and suggest steps to effectively combat it. 29/7/2019 10 Comments All About BankruptcyI. INTRODUCTION

In 2016 alone, a whopping number of 294,000 Malaysians were involved in bankruptcy cases, which is shocking to say the least.[1] To most people, the thought of being bankrupt is remote and only occurs during a bad game of Monopoly. A bankrupt person is usually perceived as either a spendthrift or someone who is horrendous at keeping tabs on his or her expenditures. Sadly, the problem of bankruptcy is more prevalent than people realise and may affect anyone regardless of their age or income. For the record, majority of bankrupts come from the age group of 25-44 years.[2] Being declared bankrupt is bad enough, but worse is how most people are in the dark about what comes after. It's an era where stars don't shine above you, because the glow of the stars is outshined by the illumination of cities. I. INTRODUCTION

Globe at Night defines light pollution as the excessive, misdirected, or obtrusive usage of artificial light and links it to the disappearance of dark skies.[1] This, in turn, affects astronomical observations, caused by excessive sky glow which results from shielded lighting, improper adjustment and unnecessary light fixtures.[2] Light pollution comes in many forms, including sky glow, light trespass, glare, and over-illumination.[3] Studies have shown that this is indeed a growing concern in Malaysia.[4] Nonetheless, is the enactment of the Light Pollution Act as purported by the Consumers Association of Penang (CAP) and initiated by the National Space Agency (ANGKASA) the only solution to curtail this issue? This article examines the legal solutions to curb light pollution in Malaysia with a comparison from other jurisdictions such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and South Korea, as well as to identify the implications of enacting and enforcing such laws on various stakeholders. Clothes are seen as necessities, and with affordable trendy outfits available at every corner in your typical shopping mall, it is almost unimaginable to think about giving any of them up. However, the reality is such that the issue of pollution wrought upon by the fast fashion industry has been prevalent for long. I. FAST FASHION: WHAT IT’S ALL ABOUT

The term ‘fast fashion’ would instinctively bring up brands like UNIQLO, H&M and Zara in our brains. You are not wrong. Fast fashion suggests that clothing collections and products, in general, change quickly. Instead of the standard four season collections, fast fashion companies have approximately 52 seasons in one year. These companies base their business models on low-cost clothing collections which emulate high-cost luxury fashion trends. They also place emphasis on rapid prototyping, efficient transportation and delivery, and ‘floor ready’ merchandise.[1] With all these elements taken into view, it is no surprise that the main attraction of fast fashion companies is the availability and affordability of their garments. Of course, to sustain this appeal, many fast fashion companies resort to outsourcing production to countries with low labour and production costs, such as Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, China and more. Companies like Zara have resorted to outsourcing at least 13 percent of their manufacturing to China and Turkey in order to suppress overhead costs. 21/11/2018 3 Comments Marital Rape: What You Need to KnowThe United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Committee called for Putrajaya to criminalise marital rape from the year 2006 onwards. However, the Malaysian government has been reluctant and slow in recognising as well as codifying marital rape as a criminal offence.

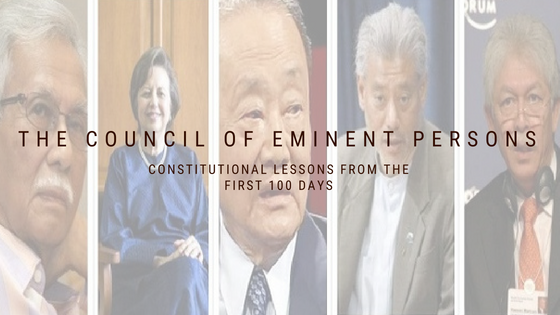

I. INTRODUCTION On International Women’s Day last year, the Women’s Aid Organization (WAO) reiterated their stance on the criminality of rape and stressed that its international standards do not cease to exist even when rape happens within a marriage. In defiance to international pressure, Malaysia has yet to ratify the criminalisation of marital rape as recommended in the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) despite being a signatory to the Convention.[1] The Council of Eminent Persons consists of former finance minister Daim Zainuddin, central bank governor Zeti Akhtar Aziz, business tycoon Robert Kuok, prominent economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram and former CEO of state oil company Petronas Hassan Marican.

I. INTRODUCTION The first 100 days of the Pakatan Harapan government have passed, and with it, any remaining traces of post-election euphoria. Amongst controversies on the new government’s actions (or lack thereof), concerns regarding the Council of Eminent Persons (CEP) stand out. This is undoubtedly due to its prominent position close to the levers of power in Putrajaya. In particular, many have begun to question its role in a maturing administration with a fully-constituted Cabinet. Such disillusionment has recalled doubts regarding its legal status, and whether its existence is contrary to constitutional principles. This essay will address both concerns in turn; arguing that the Council’s existence is both legally and normatively legitimate, before exploring the more crucial issue of how it — and the government — ought to be held accountable. Finally, it will discuss potential options for executive branch policy councils, concluding that a hybridised approach combining the structure of the National Economic Council (NEC) and Domestic Policy Council (DPC) in the United States with the treatment of special advisers as ‘temporary civil servants’ in the United Kingdom is ideal. 3/7/2018 6 Comments Tips for New PractitionersLegal practice may seem intimidating, but it is is one of the most honourable professions that one can embark upon in Malaysia.

Image credit: https://goo.gl/DKPNRT I. INTRODUCTION Entering the legal profession is the culmination of a lot of hard work. The path to professional practice in Malaysia is beset with constant challenges and seemingly endless study tasks. However, it often comes as a rude shock to young chambering students and lawyers that there are a whole lot of new skills and knowledge that they must acquire to become at least a competent legal practitioner. Those matters occupy books and books. At the same time, the psychological pressure that young practitioners feel can be intense. Hence, a practitioner must make the effort to adjust to practice as best they can while honing their skills, protecting their clients’ rights and trying not to make any costly errors. So, how can a youngster adapt while all this is happening? In what ways can a practitioner reduce the stress of their new profession? The purpose of this article is to address a number of the common issues young practitioners will face and provide practical means with which they can adjust to their new career and deal with the uncertainties and anxieties in a professional way. Homicide includes an act or an omission of a person which results in the death of another. Image credits: http://www.ferragutlaw.com/practice-areas/homicide-cases/

Dear offender, you may not intend it, but you should see this coming. I. Introduction A report from a couple of months ago on the chair-throwing incident from a flat in Pantai Dalam which had one 15-year-old boy killed in the presence of his mother had shocked the nation. I. What is online scamming and how does one get scammed?

Online scamming is a fraudulent scheme that takes money or any other goods away from an unsuspecting person through the Internet.[1] According to a survey conducted by Telenor Group, 46% of Malaysians have been a victim of online scamming compared to other countries like Thailand, India and Singapore.[2] |

|

|

PhoneTel : +603-7967 6511/6512

Fax : +603-7957 3239 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed