|

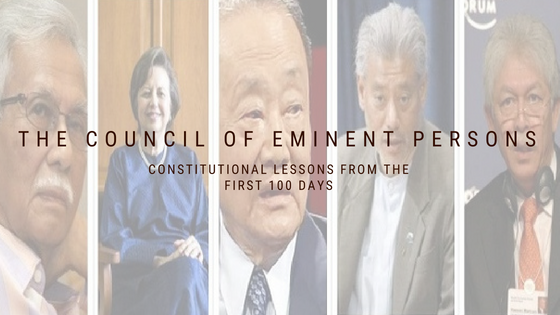

The Council of Eminent Persons consists of former finance minister Daim Zainuddin, central bank governor Zeti Akhtar Aziz, business tycoon Robert Kuok, prominent economist Jomo Kwame Sundaram and former CEO of state oil company Petronas Hassan Marican. I. INTRODUCTION The first 100 days of the Pakatan Harapan government have passed, and with it, any remaining traces of post-election euphoria. Amongst controversies on the new government’s actions (or lack thereof), concerns regarding the Council of Eminent Persons (CEP) stand out. This is undoubtedly due to its prominent position close to the levers of power in Putrajaya. In particular, many have begun to question its role in a maturing administration with a fully-constituted Cabinet. Such disillusionment has recalled doubts regarding its legal status, and whether its existence is contrary to constitutional principles. This essay will address both concerns in turn; arguing that the Council’s existence is both legally and normatively legitimate, before exploring the more crucial issue of how it — and the government — ought to be held accountable. Finally, it will discuss potential options for executive branch policy councils, concluding that a hybridised approach combining the structure of the National Economic Council (NEC) and Domestic Policy Council (DPC) in the United States with the treatment of special advisers as ‘temporary civil servants’ in the United Kingdom is ideal. II. LEGAL STATUS Facially, the Council appears to be a somewhat shadowy appendage to a now fully-constituted Cabinet of elected Members of Parliament (MPs). Even worse, some view it as operating outwith the bounds of legitimate government altogether. These negative impressions have led some to question whether the Council is a legitimate part of the administrative state at all. Such concerns are, however, unfounded. This is not to say that the status quo is optimal, but that, all things remaining equal, it does not produce constitutional tensions. If anything, it highlights the potential development of administrative and constitutional conventions relating to the position of advisors within cabinet government. Analysed reductively, it can be said that the Council does not exist as it lacks a legal basis, whether that be an Act of Parliament or ministerial prerogative.[1] Constitutionally, this is unremarkable and is legally tenable. The reason is straightforward — it has no power. Specifically, it has no public law powers. It has no legal capacity that a private individual plucked from the streets does not have. To state that it is an ‘advisory body’ is correct, but may also overplay its significance. ‘Advice’ may carry a meaning anywhere between ‘purely advisory’, ‘required consultation’, and ‘legally binding’. The latter two expressly exist in constitutional law, as in the appointment of judges, where the Yang di-Pertuan Agong has a duty to take the advice of the Prime Minister, having consulted the Conference of Rulers.[2] Formally and apparently in practice, the Council is ‘purely advisory’. It conducts consultations of its own and produces a report to be presented to the Cabinet via the Prime Minister. Cabinet ministers, as the nexus of public law powers,[3] have the discretion to accept the Council’s findings and/or advice and to implement it in their decision-making. They may do so directly by using the Council’s advice to inform their exercise of existing discretionary powers, or indirectly through the legislation of new policies and powers. Importantly, the Council’s acts itself have no legal force. In a different sense, it has no power to compel appearance or testimony. This is in contrast to Royal Commissions of Inquiry which have statutory powers to compel attendance, testimony, and the production of evidence, as well as to penalise individuals for contempt.[4] Having no such powers, The Council cannot punish individuals for their failure to appear before it. The Council and its members appear to serve at the pleasure of the Prime Minister. Although they lack formal recognition as such, it is arguable that they are analogous to political, that is, non-career civil service members of the Prime Minister’s staff. Taken alone, the fact that a minister has political and personal staff (as distinguished from civil servants) is unremarkable. Special officers and political advisers under the government’s payroll have existed for a long time. The legitimacy of their presence can, of course, be challenged, but one cannot do so without going far beyond the Council. Accordingly, so long as the Council stays within its non-jurisdiction and acts only in an advisory capacity, its existence is legally unobjectionable. III. CONSTITUTIONAL NORMS That being said, a formal reading is insufficient. A constitution is made up of not only legal rules, but also conventions and norms. Where legal rules are binding and enforceable in one way or another by the courts, the latter two are not. Conventions are constitutional in the sense that they deal with the allocation and exercise of the State’s powers, but non-binding in the sense that compliance cannot be legally enforced. A court cannot be asked to compel an individual to act in compliance of a convention. Instead, their force comes from their status as recognised patterns of practice. In other words, political expedience effectively requires compliance. Norms have a similar character, but are even less concrete. They are broader principles which underlie both rules and conventions. Taken together, conventions and norms describe the ‘oughts’ in constitutional practice. It would be proper to state that rule of law considerations are live in this case. Such a statement, however, must be disambiguated: what are the relevant facets of the rule of law? Broadly stated, the rule of law encompasses the notion that the State operates according to prescribed, accessible and enforceable laws, rather than the caprices of individuals holding public office.[5] It prescribes the government shall be one ‘of laws and not of man’.[6] More modern conceptions of the rule of law assert that that laws and legal processes be fair and just,[7] but such dimensions are not foregrounded in this case. A corollary to the proposition that the State’s powers and means for their exercise be pre-determined and predictable is that the executive’s powers must be legally restrained and limited to what is necessary. Without limits, it may act in any way it wishes. This proposition that the executive may only exercise lawfully-conferred powers in an appropriate manner is crucial to the notion of the separation of powers, which may be considered to either be a subset of the rule of law or a closely related attendant to it.[8] Although, as mentioned previously, the Council does not have powers of its own, its situation under the executive branch subjects it to the same normative constraints as ordinary members of the executive. It is evident that the Council itself does not assume any authority or influence over the judiciary (although constitutional reforms relating to the judiciary are under its mandate through the Institutional Reforms Committee[9]). Similarly, its proposals cannot take the shape of direct legislative proposals which bypass normal processes for the tabling of bills. Ultimately, this must be done through ministers qua Members of Parliament who, as in the case of their exercise of executive functions, must have the ultimate discretion in doing so. Importantly, although there may be legal remedies to potential overreaches by the Council, the modes of appropriate behaviour are conventionally and normatively regulated. The regularisation of advisors and advisory bodies cannot be achieved purely through the imposition of legal restraints, but must originate from the voluntary acceptance of normative constraints. A body such as the Council must recognise its limited standing and must be careful to stay within its constitutional boundaries. Similarly, ministers and the Cabinet must steadfastly assert their position as trustees of constitutional authority and must not abrogate their duty to act independently as holders of public office. If the Council steps outside its constitutional place, it is for the Prime Minister and Cabinet to rectify the error and accept responsibility for its occurrence. IV. ACCOUNTABILITY The same principles animate calls for the Council to operate under clear terms of reference. Arguably, the necessity for formal terms of reference is tempered as they would not define its legal jurisdiction, as would be in the case of Royal Commissions of Inquiry (RCIs), since it does not have jurisdiction regardless. Thus, terms of reference would only serve to support political accountability of its operations and output, that is, substantive accountability. Terms of reference would serve two interrelated purposes. First, to define the mandate given by the instituting minister and, second, to constitute a backstop standard of criticism of the Council’s work. Yet, when analysed closely, neither purpose requires terms of reference. The Council itself is a counter-example, albeit one whose validity as such will only be confirmed by political practices to come. The absence of specific terms takes practical effect as carte blanche terms; the Council is entrusted to define its mandate in any way it sees fit. This non-limitation is not self-prescribed, but implied by the ministerial fiat which created it. If addressed properly, there are two focal points for accountability. Firstly, the Prime Minister for the existence of the CEP in general as well as for the selection of its members and the decision to confer it a broad mandate. Secondly, the Council for the self-definition of its mandate as well as its success in undertaking it. The first point has been dealt with above. Interestingly, a closer inspection of the second reveals that, if anything, the broad mandate sets the Council up for more thorough scrutiny. Not only should its proposals on its chosen policy areas be scrutinised, but also the underlying issue of why those areas, in particular, were chosen and why others were not. In contrast, if those decisions were made by the Prime Minister, there would, in practical terms, be a ‘black hole’ of accountability where scrutiny of his mandate-setting for the Council would be crowded out by inspection of the Prime Minister’s other roles. Nonetheless, it must be reiterated that although the Council can and should be criticised on its own terms, such criticism should ultimately reflect on the minister who is responsible for its creation — notwithstanding the fact that he is (obviously) personally distinct from the Council’s members. Thus, whether there ought to be specified terms of reference is a judgment call for the Minister, with consequences on substantive accountability more minimal than what may first appear. That being said, the status quo lacks procedural accountability. Even if the Prime Minister intends for the Council to have carte blanche, the status quo is unsatisfactory as there has been no formal document issued from the Prime Minister’s Department recognising the Council’s existence, membership, structure, and temporal mandate. Such information has only been gleaned from statements by the Prime Minister and the Council’s members. V. GOING FORWARD For the future, two alternatives exist for the legitimation of advisory entities like the Council. The first would be the approach favoured by the United Kingdom (UK), whereby special advisers are made ‘temporary civil servants’[10] who are exempt from the general requirement that civil servants be selected on the basis of merit.[11] In a sense, this would be to discretise their roles into individual advisers to the Prime Minister, with the ‘Council’ emerging out of their collective existence. Although this is already applied to a limited degree in Malaysia, with ministers’ special officers treated as quasi-official members of the civil service employed by the relevant ministry or agency, current arrangements still lack necessary transparency. Where the ‘invisibility’ of career civil servants is justified by the requirement that they be politically impartial and appointed by merit, such a rationale does not apply to temporary civil servants who are appointed due to political patronage, policy expertise, or both. Thus, it would be reasonable to require — as the UK does — the government to publish annual reports on special advisers in government with details including their identities and pay grades.[12] Additionally, they should be subject to any broader reforms to the civil service, including the potential imposition of mandatory codes of practice, ethics rules, and asset disclosure requirements. Nonetheless, the apparent function of the CEP renders the approach described above inappropriate. Although it would be necessary to regulate special advisers, it is unsuited to regulate a body intended to give the government broad policy advice rather than to advise and assist ministers in their daily duties. Significantly, it does not provide a structure for its operation whether in relation to support staff, for example, the Council’s ‘Secretariat’, or inter-ministry cooperation. Thus, an arrangement similar to the United States’ National Economic Council and Domestic Policy Council, both of which are under the White House Office (analogous to the Prime Minister’s Office in Malaysia), would be more appropriate. There, the membership of councils is a combination of political appointees and the relevant Cabinet secretaries.[13] The former allows for the participation of the President’s advisers, representing his policy agenda, whereas the latter ensures that the Councils operate within the structure of Cabinet government and serves the interest of ‘joined-up government’.[14] Both approaches can also be amalgamated. Arguably, this is technically the approach taken in the United States, as the advisers directing the NEC and DPC are formally known as ‘Assistants to the President’ under the White House Office, their primary role being their directorship.[15] Thus, advisor-members of policy councils can still be categorised as ‘temporary civil servants’ and the first approach can be directly transposed underneath a Council structure. Significantly, the primary normative merit in the approaches described above is that they serve to normalise the position of ministerial advisers, and thus increase scope for their regulation. In this sense, it is arguable that the most significant defect of the Council of Eminent Persons is that it, whether deliberately or otherwise, sought to avoid charges of political interference in ministry affairs by separating itself — both literally and figuratively — from Putrajaya. Instead, the approaches adumbrated above recognise that although the work of government must happen within the normal structure of its bureaucracy, the Westminster model’s expectation that policy be formed by a handful of ministers acting alone or as part of Cabinet is untenable in the context of modern governance. Thus, reasonable accommodations must be made to facilitate their formulation of policy. In a sense, the current expectation that elected ministers alone be the initial sources of government policy is arbitrary. It appears that we trust their personal judgment to decide matters of the State, except for where that judgement is that they require the advice of other individuals with subject-matter expertise. This is precisely the tension highlighted by the Council — that we may trust the Prime Minister and those he selects from the ranks of MPs as Ministers, but not those he selects from outside Parliament. Although it is true that the latter lack democratic legitimacy and accountability, such an argument is a red herring. The Council is not a manifestation of democratic government per se, but that of the Prime Minister’s own policy direction to the extent that he cannot represent or formulate it on his own. Consequently, the Council has legitimacy through the Prime Minister, an acceptable arrangement given that he, and Cabinet, are accountable for its actions and are the formal sources of policy and power. VI. CONCLUSION Going forward, there ought to be a space for legitimate and transparent fora within the government for the formulation of policy. The Council itself, as a widely-publicised and well-known entity, should serve as a starting point for the development of best practices in that regard. Although its institutional set-up can be improved, the Council is still far from being unconstitutional. At the risk of giving praise for the attainment of minimal standards, its relatively transparent existence is a welcomed development from past administrations’ practices in relation to advisory bodies. Although stating that there is a normative shift in favour of increased transparency in the nether regions of the administrative state is nascent overstating reality, the Council’s acts and reactions to it from the government, MPs, the media, and the general public may be indicative of the potential for such shifts to occur in the future. One can only hope that the Council’s reports do not remain internal Cabinet documents; they should be disclosed to the public and, ideally, be tabled before the Houses of Parliament for formal debate. In a similar vein, the reports should not be limited to the Council’s substantive findings and recommendations, but also include details on its consultation methodology and consultees. By doing so, the Council may provide its own contributions towards emergent conventions in favour of an open and accountable government. Written by Shukri Shahizam, a third-year LL.B student of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and Editor-in-Chief of the LSE Law Review. The author conveys his thanks to Tan Kian Leong and Marie Lim Shu Fei for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. Edited by Caysseny Tean Boonsiri. Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Malaya Law Review, and the institution it is affiliated with. Footnotes:

[1] In Pythonesque terms, it is a non-Council. See: “Dead Parrot Sketch”, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, BBC, London, 7 Dec. 1969. [2] Malaysian Constitution, Art. 122B(1). [3] Malaysian Constitution, Art. 43. [4] Commissions of Enquiry Act 1950 (Act 119), s. 12-17. [5] Dicey, AV, “The Rule of Law: Its Nature and General Applications”, An Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (London: Macmillan 1915), p. 107-122. [6] A quotation often attributed to John Adams, and finds codification in Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Article XXX of Part the First. [7] Bingham, T, The Rule of Law (London: Allen Lane 2010). [8] Allan, TRS, “First Principles: the Rule of Law and Separation of Powers”, Constitutional Justice: A Liberal Theory of the Rule of Law (Oxford: OUP 2003), p. 33-60. [9] Committee for Institutional Reforms, Terms of Reference (Kuala Lumpur 2018). [10] Cabinet Office, Code of Conduct for Special Advisers, s. 4. [11] Civil Service Order in Council 1995, Art. 3. [12] Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010, ss. 15-16. [13] Executive Order 12835, s 2; Executive Order 12859, s. 2. [14] Foster, C, “Joined-Up Government and Cabinet Government”, Ed., Vernon Bogdanor, Joined-up Government (OUP 2005), Ch 5. [15] Executive Order 12835 s. 3; Executive Order 12859, s. 3.

1 Comment

13/6/2019 07:56:50 pm

Nearly a year after this comment was published perhaps it is clearer why the deliberations of the CEP have been kept confidential: the government cannot be criticised for its non-action in relation to any recommendations given by the Council.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

|

PhoneTel : +603-7967 6511/6512

Fax : +603-7957 3239 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed